Two big shifts are under way in the world of software development. Since the launch of Chatgpt in 2022, bosses have been falling over themselves to try to find ways to use generative artificial intelligence (AI) productively. Most efforts have so far yielded little, but one exception is software programming. Surveys suggest that developers around the world find generative ai so useful that already about two-fifths of them use it.

The profession is changing in another way, too. A growing share of the world’s engineers come from emerging markets. There is no standard definition of a developer, but around 2020 the number of users of Github, a popular platform for storing and sharing code, living in poorer countries surpassed those from the rich world. On the same measure, in the next few years India is expected to overtake America to become the world’s biggest pool of programming talent (see chart 1).

These shifts matter because software talent is treasured. Salaries are high (see chart 2). The median wage of a developer in America sits in the top 5% of all occupations, meaning that coders earn more than nuclear engineers. Tech giants need them to make their platforms more attractive; non-tech company bosses want ever more coders to aid the digitisation efforts that, they hope, will improve productivity and appeal to consumers. The two shifts are therefore welcome news. The future looks to be one with more, and more productive, coders—and cheaper software.

New technologies have often aided developers. The internet, for instance, ended the time-consuming task of answering questions using textbooks. Generative ai looks like a bigger leap forward still. One reason why it can be especially useful for developers is the availability of data. Online forums, such as Stack Overflow, hold enormous archives of questions asked and answered by coders. The answers are often rated, which helps ai models learn what is helpful and what is not. Coding is also full of feedback loops and tests that check if software works properly, notes Nathan Benaich, of Air Street Capital, a venture-capital (vc) firm. ai models can use this feedback to learn and improve.

The consequence has been an explosion of new tools to help programmers. PitchBook, a data provider, tracks some 250 startups making them. Big tech is leading the charge. In June 2022 GitHub, which is owned by Microsoft, launched Copilot. Like many tools it can, when prompted, spit out lines of code. Around 2m people pay for a subscription, including employees at 90% of Fortune 100 firms. In 2023 Alphabet (Google’s parent company) and Meta (Facebook’s parent) released rivals. This year Amazon and Apple followed suit. Many firms have built ai coding tools for internal use, too.

ai’s helpfulness is still somewhat limited, however. When Evans Data, a research firm, asked coders how much time the technology tends to save them, the most popular answer, given by 35% of respondents, was between 10% and 20%. Some of this is from churning out simple “boilerplate” code, but the tools are not perfect. One study from GitClear, a software firm, found that over the past year or so the quality of code has declined. It suspects the use of ai models is to blame. A survey by Synk, a cybersecurity firm, found that more than half of organisations said they had discovered security issues with poor ai-generated code. And ai still can’t tackle the thornier programming problems.

The next generation of tools should be better. In June Anthropic, an ai startup, released its newest model, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, which is better than predecessors at, among other things, coding. On September 12th Openai, the maker of Chatgpt, launched a version of its latest model, o1, claiming that it “excels at accurately generating and debugging complex code”.

ai tools can increasingly help with other mundane tasks (“toil” in coder-speak), such as writing notes about what the code does or designing tests to make sure code won’t malfunction. Writing code is only a part of the job of a software engineer, accounting for about 40% of their time, according to Bain, a consultancy. The tools might also help programmers become more flexible by switching between coding languages faster, allowing them to apply their skills to different situations more easily. Euro Beinat, of Prosus, an investment firm, says that he has seen engineers move from one language to another in a week rather than three months. Amazon recently said that it saved $260m when it converted thousands of applications from one type of code to another using ai.

The new-found flexibility extends to different types of programming. A small app may previously have required a team of six working on different parts of the programme, such as the user interface or the software’s plumbing. Jennifer Li, of Andreessen Horowitz, a big vc firm, says she is seeing more startups with fewer people, as programmers can more easily take on many different tasks. Plenty of it managers say that training newly hired developers on the idiosyncrasies of their firm’s software is getting faster, too.

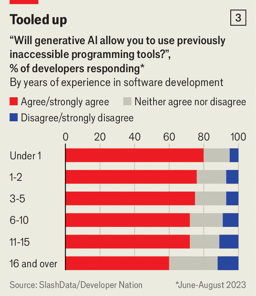

Much of this seems to give inexperienced engineers a leg up (see chart 3). They will be able to do more complex tasks more quickly and some of the work they used to do may be picked up by laymen. A rising trend toward “low-code-no-code” platforms, which allow anyone to write software, will also be boosted by ai. Banco do Brasil, a lender in Brazil, has been using such a system to allow employees to develop hundreds of apps, such as ones which make it easier to help customers seeking insurance products.

Another result of the coding upheaval is that junior developers in rich countries will face more acute competition from abroad. According to Evans Data, between 2023 and 2029 the number of computer programmers in the Asia-Pacific region and Latin America is expected to rise by 21% and 17% respectively, compared with 13% in North America and 9% in Europe. The imbalance means a boom in offshoring and outsourcing is likely to continue. Everest, a consultancy, reckons that about half of all it spending is outsourced, including lots of software development. Other firms that have kept it services in house have instead set up their own outposts abroad, to take advantage of lower wage costs. India is the world’s powerhouse. In 2023 exports of software and related services amounted to $193bn, with half going to America.

This helps companies control costs. “It is a very good way of scaling out…without blowing up budgets,” says Shashi Menon, who is in charge of the digital efforts for Schlumberger, an oil-and-gas services firm. About half of his engineering team are based in Beijing and Pune in India.

Offshore capabilities have been growing more sophisticated. Some foreign outposts now provide basic software as well as high-end fare. Sanjeev Jain of Wipro, an Indian firm, says his engineers helped build Teams, Microsoft’s video-streaming service, as well as designing chips and software for “connected cars”, which speak to other services and devices. ai could help offshore firms produce snazzier software; ai nous itself is also something they can sell. Infosys, another Indian firm, recently said that it had won a $2bn five-year contract to supply ai and automation services to an unnamed client.

What all this means for developers is still unclear. One vision is of ai and offshoring taking Western software developers’ jobs en masse. That seems far-fetched. Huge amounts of technical know-how are still required to string pieces of code together and check that it works.

A more optimistic view is one in which the most boring parts of making software are done by computers while a developer’s time is spent on more complex and valuable problems. This may be closer to the truth. For customers, meanwhile, the trends are welcome. it managers have long said that their bosses want ever more digitisation with ever tighter budgets. Thanks to ai and offshoring, that may no longer be too much to ask.■