Many investors will have greeted the start of corporate America’s latest earnings season feeling chipper. After a brief wobble in the first half of last year, the profits of big American firms in the S&P 500 index have climbed steadily higher in each subsequent quarter. This time around their profits are expected to grow by a bit more than 4%, year on year.

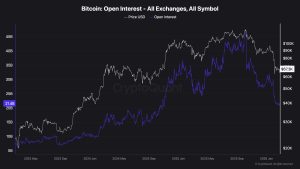

Faced with fat profits in the present—and the promise of fatter ones in the future thanks to artificial intelligence (AI)—investors have sent the S&P 500 index up by 23% this year, its strongest performance since 1997. Valuations are now at eye-watering levels: at 22 times forward earnings, the yield on stocks is comparable to that of America’s government debt (see chart 1). What could go wrong?

One place to look for threats is the earnings season. So far, however, that has made investors only more bullish. The fifth of firms in the S&P 500 that have already reported their results have easily beaten expectations—even as chief executives have signalled caution. Jamie Dimon, the boss of America’s biggest bank, affixed a bleak warning to the front page of JPMorgan Chase’s earnings print. Geopolitics and spiralling government debt, he wrote, pose a serious threat to the economy. The bank’s stock nonetheless rose by 5%. Investors seemed to read Mr Dimon’s musings more as a pitch to be America’s next treasury secretary than an earnest warning.

As interest rates come down, lending margins for banks like Mr Dimon’s are being squeezed. Yet cheaper debt also means more companies raise money and strike deals, providing juicy fees. At Goldman Sachs, for instance, investment-banking revenue in the most recent quarter was up by a fifth year on year, more than twice as much as expected.

Worries of a collapse in consumer spending are also fading. Pessimists may point to results from Ally Financial, the lender that was split off from General Motors, which significantly increased its provisions for bad car loans. The number of Americans not paying these off is now at levels seen during the financial crisis. Other signs, however, suggest America’s consumers remain indefatigable. Cheaper ad-supported subscriptions have buoyed Netflix; premium credit cards have lifted American Express. National retail-sales figures rose for the third straight month in September.

Corporate America has been propped up in part by surging profits among its technology giants, which are yet to report their results for the quarter. Nvidia, the biggest beneficiary of the Ai boom, is expected to account for 13% of all profit growth in the S&P 500 this year. Add its six famous cousins, which together make up the “magnificent seven” stocks, and that figure rises to 62%. Exclude all seven and the S&P 500’s earnings recession ended not in the third quarter of 2023, but only in the second quarter of this year.

Investors are now betting that America’s profit bonanza will become more evenly shared. Profits among the S&P 493 next year are expected to grow by 13%. The Russell 2000 index of smaller listed companies is also trading above its long-run valuation multiple, suggesting that investors are bullish not only about the outlook for America’s corporate giants but about its middling companies, too.

That is a bold call. To those with a historical bent, it looks like a foolish one. When tallied as a share of GDP, profits have been on a 40-year bull run (see chart 2). In a paper published last year Michael Smolyansky, a researcher at the Federal Reserve, showed that the acceleration in America’s profit growth from 1989 to 2019 was “entirely due to the decline in interest and corporate-tax rates”. That suggests that the outlook for corporate profits will hinge on the decisions of central bankers and politicians.

Since the Fed began raising interest rates in 2022, big American firms have been shielded from the rising cost of financing, protected by high cash balances and long-dated bonds paying low, fixed coupons. The IMF has shown that from 2021 to 2023 net interest expenses of non-financial American companies fell even as interest rates rose. Smaller firms, including the highly indebted ones owned by private-equity funds, were less fortunate. Like European companies, they rely more on floating-rate bank loans than on bonds.

The holiday for big American firms, though, is coming to an end. The Federal Reserve may be reducing its benchmark rate, but few expect a return to the record lows of the past decade. American firms owe $2.5trn worth of fixed-coupon bonds due before the end of 2027. For the $840bn of that pile owed by non-financial firms in the S&P 500 index, the median coupon is 3.4%; the yield to maturity, a proxy for the minimum rate firms will have to offer when they refinance these debts, is 4.5%. What is more, the spread between the yields of investment-grade corporate bonds and government debt is historically low, at just above 0.8 percentage points. If it widens, the cost of refinancing will soar.

The outcome of America’s presidential election could also slow America’s profit juggernaut. Donald Trump, whose chance of victory has been rising, promises a sugar rush if he returns to the White House. During his first presidency he cut the statutory corporate-tax rate from 35% to 21%. He wants to lower it further, perhaps to 15%. That would be a big boost to profits: each percentage-point decrease in the statutory rate lifts s&p 500 earnings by nearly 1%, reckon analysts at Goldman Sachs. Yet this will have to be weighed against the dangers Mr Trump poses in the longer term. His promise to levy hefty tariffs may cover some companies in protectionist bubble wrap, but others will find their profits squashed if they are unable to pass higher costs on to consumers. His disregard for institutions, meanwhile, could cause confidence in America’s markets to rot.

A Kamala Harris presidency would not pose such nightmarish threats. But nor would it give businesses a sugar rush. If her predecessor’s record is any guide, Ms Harris will continue to frustrate profit-pumping mergers among big American companies and may even seek to break some up. Even more worrying for bosses, she has proposed raising the corporate tax rate to 28%. Ms Harris would need a majority in both houses to make that happen, something that polls today suggest is unlikely. Still, even if lots of voters are waiting for the campaigning to be over, corporate titans may be happier with things as they are. ■