Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

Since the first iPhone fell into people’s pockets in 2007, apps have steadily become the portal of choice to the digital world. The mobile devices on which they run now account for two-thirds of global internet traffic. Inhabitants of rich countries spend about five hours a day staring at apps—roughly a third of their waking lives. Around the world some 3.5bn people use them each month.

That has made the app stores that distribute them a lucrative business for Apple and Alphabet, the tech titans whose iOS and Android operating systems power the vast majority of the world’s mobile devices. That, in turn, has drawn the attention of governments. They are leaning on the duopoly to limit access to disfavoured apps while at the same time working to loosen its stranglehold over the market. They risk irking consumers on both counts.

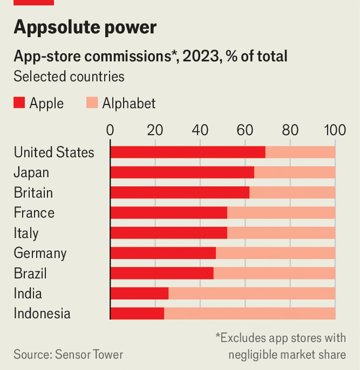

Apple and Alphabet keep the financial details of their app stores close to their chests. These make money in a variety of ways. The biggest chunk comes from charging a 30% fee on the sale of digital goods, such as snazzy outfits and supercharged weapons for avatars in video games. The stores also take a cut of app subscriptions, usually at the lower rate of 15%. Sensor Tower, a data firm, estimates that Apple took in $27bn and Alphabet $13bn from these types of commission last year, though their market shares vary across countries (see chart). Analysts reckon the pair also made several billion dollars each selling ads that appeared next to app-store search results.

That may not seem like much when compared with Apple’s and Alphabet’s nearly $700bn in combined revenues last year. Most of the app-store bounty, however, falls straight to the firms’ bottom lines. Court documents from recent years suggest an eye-popping operating margin of around two-thirds for Alphabet’s app store and four-fifths for Apple’s.

Governments seeking greater control over the digital world are increasingly doing so via these gatekeepers. The number of requests Alphabet has received from regulators and courts to remove apps from its Google Play store rose from 496 in 2019 to 1,743 last year. In 2022 Apple removed 1,474 apps from its store on the basis of such requests, up from 558 in 2019. Most of these requests came from the Chinese government. For Alphabet, which does not operate its app store in the country, most came from India.

The reasons for such requests vary. Some aim to limit access to content such as pornography or depictions of suicide. Others are about censoring dissent. In April China’s government demanded that Apple remove messaging apps including WhatsApp and Telegram from the local version of its app store. A growing number of requests are geopolitically tinged. Last month Joe Biden signed a law that would compel American app stores to ban TikTok, an addictive short-video app, if ByteDance, its Chinese owner, does not divest its operations in America within nine months. The legislation has riled many of TikTok’s users. On May 7th the company filed a petition in federal court claiming a ban is unconstitutional. The app is already blocked in India.

At the same time, governments are trying to pry open the app-store duopoly. Among other things, the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) compels the tech firms to allow other app stores to be used with their operating systems, a freedom Apple has not previously granted iPhone users. Japan’s government is trying to pass a bill with a similar aim. Britain is probing the app-store business, too. India’s government is so eager to introduce competition to the market that it has considered launching its own app store.

Plenty of developers are on their side. In 2019 Spotify, a music-streaming service, lodged a complaint in the EU against Apple for, among other things, barring it from telling customers they could get a lower price by signing up for their subscription outside the app. In March the EU slapped Apple with a €1.8bn ($2bn) fine after concluding its investigation into the matter. Epic Games, a video-game developer, has sued Apple and Alphabet in America on antitrust grounds. On most counts it lost its case against Apple, but in December a jury sided with it in its suit against Alphabet, concluding that the Google Play store operates as an illegal monopoly. The judge is still to decide on the resulting remedies, and Alphabet has said it will appeal against the verdict. Meanwhile, Epic is also suing Apple and Alphabet in Australia and Britain on similar grounds.

Regulators and developers hope the upshot of all this will be more competition and lower fees. Last year Phil Spencer, the boss of gaming at Microsoft, another tech giant, described the DMA as a “huge opportunity” and said that his company plans to launch app stores on iOS and Android. Epic wants to do the same. Some also hope for a burst of innovation, and talk of the possibility of, say, child-friendly app stores, where all software is carefully vetted. On April 17th AltStore, an alternative app store, became available to iPhone users in Europe. So far it has two apps. One lets users play games made for Nintendo consoles on their phones. The other helps users manage snippets of text they have copied recently.

Others, however, point to possible pitfalls. They worry that unwholesome niche stores focused on things like pornography or online gambling will proliferate—leading to more of the very content that some governments have been cracking down on. In China local smartphone-makers, such as Huawei and Oppo, run their own popular app stores and may be temped to expand into Europe. China-bashing politicians will doubtless dislike that.

In exchange for their fees, Apple and Alphabet also provide important services to developers, especially smaller ones. That includes vetting new apps for bugs and malicious software, which gives consumers the confidence to use apps without fear of being fleeced. Many users also seem to value the convenience of the one-stop app shops that Apple and Alphabet already provide. Tellingly, even though Android phones have always allowed alternative app stores, no serious contenders to Google Play have emerged. A rival offering launched by Amazon, another tech giant, in 2011 gained little traction.

Consumers, then, hardly seem to be crying out for change. As a result, disruption will be slow. Those who want to shake up the market may have to wait for the next whizzy device to come along. As long as the age of the smartphone endures, so too, it seems, will the app-store duopoly. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.