Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

For years BHP and Rio Tinto, the world’s two most valuable miners, moved in lockstep. During the 2000s the twin Anglo-Australian giants rose on the back of China’s demand for commodities, particularly iron ore. In 2007 they even explored a merger (regulators rebuffed the idea). Then, when the commodity supercycle crashed in 2015, both landed in investors’ bad books, and were forced to shed assets and pay down their debts. Now, as the pair look to make the most of the energy transition, they are placing diverging bets on the future.

On October 9th Rio, the smaller of the two by market value, announced it was buying Arcadium Lithium for $6.7bn in one of the largest mining deals of the past decade. The purchase will make Rio the world’s second-biggest producer of lithium, a critical element in batteries, with mines from Argentina and Australia to Canada and China. It follows various other lithium investments by the company in recent years, including the acquisition of a site in Argentina for $825m in 2022 (expected to begin production before Christmas) and a project in Serbia that has been delayed by a backlash over its potential environmental impact.

Rio’s bet on lithium is bold. Prices of the metal have plunged by more than 80% over the past two years as the market for electric vehicles has decelerated and concerns around oversupply have spooked traders. Yet Jakob Stausholm, Rio’s boss, is confident that demand for lithium will outpace supply over the course of the decade, leading prices to rise again. He adds that Rio’s mines will be better quality and lower cost—and therefore more profitable—than those of its competitors. The acquisition of Arcadium should help with that: the miner is a pioneer in so-called direct lithium extraction, a group of technologies that draw lithium from brine without relying on evaporation, which is less efficient.

“Lithium is a differentiator between Rio and all the other big miners,” says Mr Stausholm. That includes BHP. Mike Henry, the bigger miner’s boss, has said in the past that he doesn’t “see the opportunity” in lithium. He is more interested in copper, a metal that is also critical to the energy transition as well as to the data centres powering the artificial-intelligence revolution. Earlier this year BHP tried to buy Anglo American, another big miner, for $39bn, primarily for its copper assets. After that fell through, it announced it would buy Filo Corp, an exploration company with copper assets, for about $3bn, in partnership with Lundin Mining, a Canadian miner. Although Rio has also invested in copper, it produces far less of it than BHP.

Aluminium is another area in which the two have diverged: BHP divested its aluminium business a decade ago; since then Rio has continued to expand its role in the West’s supply chain for the metal. It is now one of the world’s biggest miners of bauxite, the ore that is refined into aluminium. On October 16th Rio reported it produced 15m tonnes of the stuff in the quarter from July to September, up about 8%, year on year. Last year the company said it would invest $1.1bn to expand its aluminium smelting operations in Quebec. And earlier this year it acquired a 50% stake in a producer of recycled aluminium for $700m.

On the whole, Rio has been far more aggressive in its pursuit of growth than its rival. Besides BHP’s investments in copper and, to a lesser extent, nickel and potash, it has kept its purse-strings tight. The book value of its operating assets is roughly what it was in 2019; Rio’s, by contrast, has surged by a fifth over that period. As BHP has concentrated more on mines in Australia, Rio has made investments in far-flung places from Guinea to Mongolia. The pair’s preferred commodities are also telling. Lithium’s price may be more volatile than copper’s, and its market currently smaller, but demand could rocket: the International Energy Agency, an official forecaster, predicts that in a net-zero scenario demand for lithium in 2040 will be about 8.7 times its level today, compared with 1.5 times for copper.

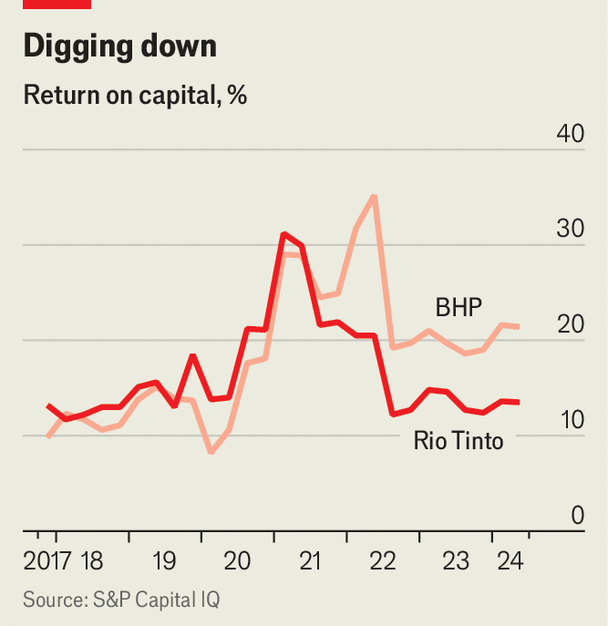

Rio’s focus on expansion, however, has come at a cost. In 2019 the return on capital for the two miners was almost identical, at roughly 15%; Rio’s has since fallen to below 14% while BHP’s has risen to 21% (see chart). To surpass its long-standing rival, Rio will need to find ways to turn more of its earth into profit. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.