Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

Jensen Huang is a man on a mission—but not so much that he does not have time to tell a good story at his own expense. Last spring, when his semiconductor company, Nvidia, was well on its way to becoming a darling of generative artificial intelligence (AI), he and his wife bought a new home in the Bay Area. Mr Huang was so busy he could not spare much time to visit it before the purchase was completed. Pity, he admitted later, sneezing heavily. It was surrounded by plants that gave him hay fever.

Mr Huang uses such self-deprecating humour often. When he took to the stage on March 18th for Nvidia’s annual developers’ conference, to be greeted by cheers, camera flashes and rock-star adulation from the 11,000 folk packed into a San Jose ice-hockey stadium, he jokingly reminded them it wasn’t a concert. Instead, he promised them a heady mix of science, algorithms, computer architecture and mathematics. Someone whooped.

In advance, Nvidia’s fans on Wall Street had dubbed it the “AI Woodstock”. It wasn’t that. The attendees were mostly middle-aged men wearing lanyards and loafers, not beads and tie-dyes. Yet as a headliner, there was a bit of Jimi Hendrix about Jensen Huang. Wearing his trademark leather jacket, he put on an exhilarating performance. He was a virtuoso at making complex stuff sound easy. In front of the media, he improvised with showmanship. And for all the polished charm, there was something intoxicating about his change-the-world ambition. If anyone is pushing “gen AI” to the limits, with no misgivings, Mr Huang is. This raises a question: what constraints, if any, does he face?

The aim of the conference was to offer a simple answer: none. This is the start of a new industrial revolution and, according to Mr Huang, Nvidia is first in line to build the “AI factories” of the future. Demand for Nvidia’s graphics-processing units (GPUs), AI-modellers’ favourite type of processor, is so insatiable that they are in short supply. No matter. Nvidia announced the launch later this year of a new generation of superchips, named Blackwell, that are many times more powerful than its existing GPUs, promising bigger and cleverer AIs. Thanks to AI, spending on global data centres was $250bn last year, Mr Huang says, and is growing at 20% a year. His company intends to capture much of that growth. To make it more difficult for rivals to catch up, Nvidia is pricing Blackwell GPUs at $30,000-40,000 apiece, which Wall Street deems conservative.

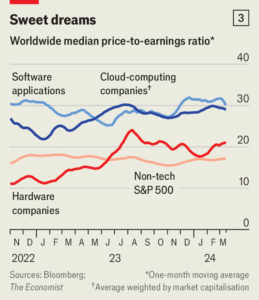

In order to reap the fruits of this “accelerated-computing”, Nvidia wants to vastly expand its customer base. Currently the big users of its GPUs are the cloud-computing giants, such as Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft, as well as builders of gen-AI models, such as OpenAI, maker of ChatGPT. But Nvidia sees great opportunity in demand from firms across all industries: health care, retail, manufacturing, you name it. It believes that many businesses will soon move on from toying with ChatGPT to deploying their own gen AIs. For that, Nvidia will provide self-contained software packages that can either be acquired off the shelf or tailored to a user’s needs. It calls them NIMs, Nvidia Inference Microservices. Crucially, they will rely on (mostly rented) Nvidia GPUs, further tying customers into the firm’s hardware-software ecosystem.

So far, so star-spangled. But it is not all peace and love at Woodstock. You need only to recall the supply-chain problems of the pandemic, as well as the subsequent Sino-American chip wars, to see that dangers lurk. Nvidia’s current line-up of GPUs already faces upstream bottlenecks. South Korean makers of high-bandwidth memory chips used in Nvidia’s products cannot keep up with demand. TSMC, the world’s biggest semiconductor manufacturer, which actually churns out Nvidia chips, is struggling to make enough of the advanced packaging that binds GPUs and memory chips together. Moreover, Nvidia’s larger integrated systems contain around 600,000 components, many of which come from China. That underscores the geopolitical risks if America’s tensions with its strategic rival keep mounting.

Troubles may lie downstream, too. The AI chips are energy-hungry and need plenty of cooling. There are growing fears of power shortages because of the strain that GPU-stuffed data centres will put on the grid. Mr Huang hopes to solve this problem by making GPUs more efficient. He says the mightiest Blackwell system, known pithily as GB200NVL72, can train a model larger than ChatGPT using about a quarter as much electrical power as the best available processors.

But that is still almost 20 times more than pre-AI data-centre servers, notes Chase Lochmiller, boss of Crusoe Energy Systems, which provides low-carbon cloud services and has signed up to buy the GB200NVL72. And however energy-efficient they are, the bigger the GPUs, the better the AIs trained using them are likely to be. This will stoke demand for AIs and, by extension, for GPUs. In that way, as economists pointed out during a previous industrial revolution in the late 19th century, efficiency can raise power consumption rather than reduce it. “You can’t grow the supply of power anything like as fast as you can grow the supply of chips,” says Pierre Ferragu of New Street Research, a firm of analysts. In a sign of the times Amazon Web Services, the online retailer’s cloud division, this month bought a nuclear-powered data centre.

’Scuse me while I kiss AI

Mr Huang is not blind to these risks, even as he dismisses the more typical concerns about gen AI—that it will destroy work or wipe out humanity. In his telling, the technology will end up boosting productivity, generating profits and creating jobs—all to the betterment of humankind. Hendrix famously believed music was the only way to change the world. For Mr Huang, it is a heady mix of science, engineering and maths. ■

If you want to write directly to Schumpeter, email him at [email protected]

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.