It’s not easy being a customer-service agent—particularly when those customers are so angry with a product that they want to yell at you down the phone. That’s the sort of rage that Sonos, a maker of home-audio systems, encountered in May when it released an app update so full of glitches it caused its share price to plunge.

One of the agents dealing with the ensuing customer tirades was a rookie. But not a human one. Prior to the debacle, Sonos had hired Sierra, a startup co-founded by Bret Taylor, the chairman of OpenAI, to provide it with a customer-service bot powered by generative artificial intelligence (AI). It could have been a disaster; the only thing worse than a malfunctioning product is being trapped in an automation prison by a robot giving you the runaround. Yet the bot beat expectations. After digesting Sonos’s technical materials, it even came up with its own workaround for one of the problems with the Sonos app.

Customer service is one of the few industries where the use of generative AI is already taking root. In a survey of customer-service executives published earlier this year by Gartner, a research firm, almost half said that AI customer assistants would have a significant impact on their organisation in the next 12-18 months. Startups and established tech firms alike have launched a volley of new products at the industry that promise to transform customer service—and millions of jobs.

Customer service is a big industry. Most companies have some sort of customer support, whether in-house or outsourced to call centres. In America alone there are almost 3m customer-service workers, according to the Bureau of Labour Statistics. At a median salary of around $40,000 a year, that works out at roughly $120bn in wage costs. Many more work in call centres in places like India and the Philippines, where these jobs are seen as ladders to the middle class.

In recent years, however, the industry has become notorious for driving customers mad with its use of technology. Its poor reputation is deserved, reckons Andy Lee, co-founder of Alorica, an American contact-centre business with 100,000 employees. Because it is expensive for firms to use humans to solve their customers’ problems, they make the process as cumbersome as possible by forcing you to press a bewildering combination of numbers or chat with a bot that regurgitates generic responses, a strategy that in the industry is called “deflection”. Once human agents are involved, it is in the financial interests of outsourcing firms to make the process as labour intensive as possible, further raising costs and frustrating everybody.

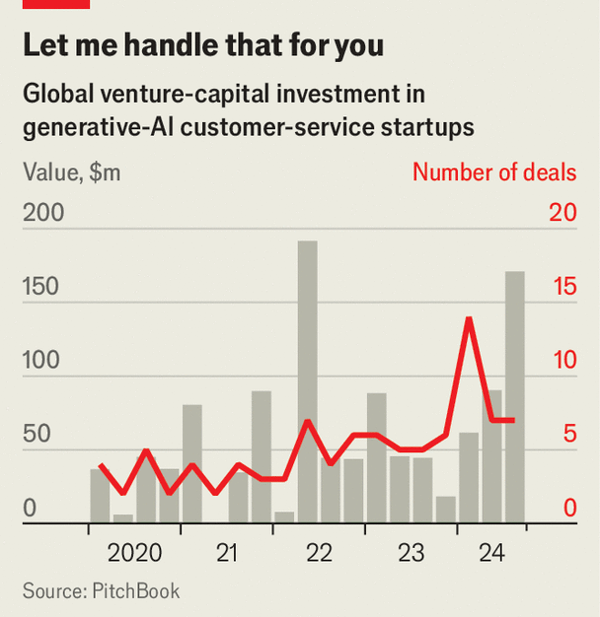

Now entrepreneurs and venture capitalists are betting that generative AI can make it all less awful. Funding for startups developing customer-service tools that use generative AI reached $171m globally in the third quarter, up from $45m the year before, according to PitchBook, a data gatherer (see chart). Earlier this month Crescendo, co-founded by Alorica’s Mr Lee, raised money at a valuation of $500m. Sierra, which raised money at a valuation of about $1bn in February, is now said to be seeking more at a valuation of $4bn, raising eyebrows even among some AI-crazed venture capitalists.

It is not just startups entering the field. Tech titans like Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft are bringing generative AI to their customer-service offerings. Software firms like Salesforce are too. Some companies are also using large language models like those produced by OpenAI to create their own customer-service bots.

Unlike their rote-learning predecessors, generative-AI bots do not regurgitate canned answers to narrow questions. Instead, they create their own responses informed by the firms’ training materials and previous customer-service interactions.

Providers are divided on the role these bots should play. One approach, advocated by Crescendo, is for humans to continue managing conversations with customers with an AI buddy in the background giving tips. But plenty of others think that generative-AI bots are now clever enough to handle most conversations themselves. This month Twilio, which provides tools for customers to communicate with companies, announced it will launch a customer-service bot that can listen and talk, rather than merely read and type. A number of generative AI startups in the industry have adopted “outcome-based pricing”, charging for their technology when a customer query is resolved, rather than per agent or minute of interaction, as is standard.

That raises two knotty questions. One is how customers feel about all this. Advocates for the technology say that customers will no longer have to wait endlessly for a person to pick up the phone, and point out that bots will be fluent in many languages and have easier-to-understand accents than foreign call-centre agents. Customers, though, are yet to be convinced: 64% of those surveyed by Gartner said they would prefer it if companies didn’t use AI for customer service, mostly because they worry it will make it even more difficult to reach a human. People still value human-to-human contact, insists Rob Goeller, co-founder of Clearsource, a customer-service firm based in Utah with employees in America, Costa Rica, India and the Philippines.

What is more, generative-AI bots have a tendency to project utter confidence in their responses even when they are wrong, which could wreak havoc. Earlier this year Air Canada was forced to compensate a customer who was incorrectly promised a discount by the airline’s AI chatbot.

A second question is what all this means for the jobs of call-centre agents. Last year Gartner predicted that generative AI would lead to a 20-30% reduction in customer-service jobs by 2026. For now, Mr Goeller says Clearsource is focused on using generative AI to help train its human agents and assist with summarising calls. But he adds, “I would be putting my head in the sand if I said [generative AI] wouldn’t replace people.”

Previous waves of customer-service technology, including email and those pesky voice menus, stoked concerns about job losses, only for them to fail to materialise. AI could yet prove different. And if it does, its effects may be salutary. Human agents could be freed up to spend more time on creative and rewarding tasks, like using feedback to make products better—and less time listening to irate customers. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.