Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

BETWEEN 2021 and 2023 two parts of the drugmaking business were in contrasting states of health. An index of American big pharma rose by a third, outperforming the broader stockmarket thanks to robust sales of blockbuster drugs. One made up of smaller biotechnology companies sank by roughly as much, weighed down by rising interest rates and dissipating pandemic-era euphoria for all things medical. Unlisted biotech startups have, like most young firms, struggled to attract capital. Last year they drew just $17bn in investments, down from $37bn two years earlier. Fewer went public and more went bust.

This year the giants are still going strong. On April 30th Eli Lilly, maker of a popular weight-loss treatment, delivered another dose of strong quarterly results. On May 2nd Novo Nordisk, a Danish rival with its own hit anti-obesity drug, did the same. Together the two are worth $1.2trn, up from $350bn three years ago. But biotech’s vitals, too, are improving. That is good news for investors, patients and the pharmaceutical industry as a whole.

In the first three months of 2024 investors injected $5.1bn into biotech startups, the most in seven quarters. Eight companies have launched initial public offerings (IPOs) since January, raising a combined $1.5bn, compared with $2.5bn for all those that listed in 2023. Another nine have sold themselves to larger drugmakers for $1bn or more—the busiest start to a year in a decade. In February Novartis, a Swiss pharmaceutical titan, said it intended to buy MorphoSys, a German cancer specialist, for $2.9bn. The following month AstraZeneca, a British-Swedish giant, acquired two biotech firms for over $3bn. IQVIA, a research firm, expects $180bn-200bn in biotech and pharma deals this year, up from $85bn in 2022.

One reason for the revival is the painful triage of the past two years. Many firms with bleak prospects were eliminated; the number of biotech bankruptcies in 2023 was the highest in a decade. Those that remain are sturdier on average. Their more down-to-earth valuations also make them more appealing takeover targets for cash-rich big pharma. Fifteen of the world’s largest drugmakers have a collective $800bn at their disposal for mergers and acquisitions, IQVIA calculates.

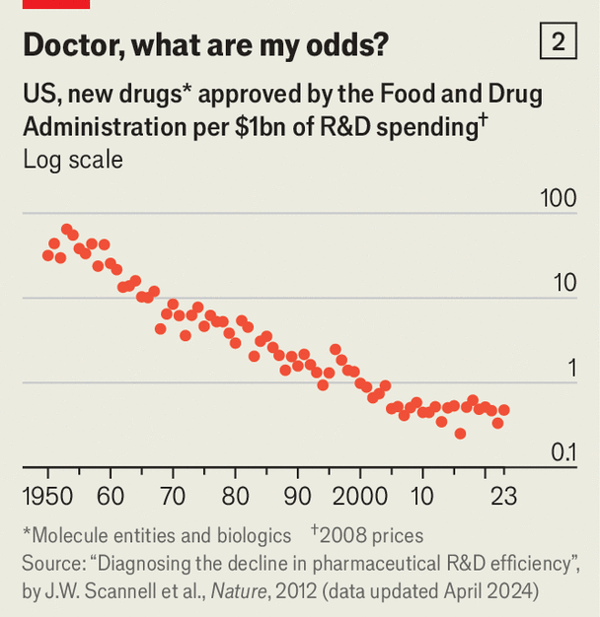

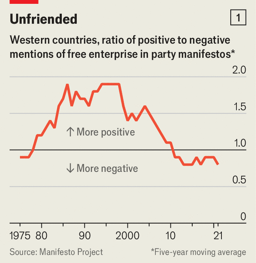

They are eager to put this money to use, especially as many of their lucrative patents are about to expire. In 2028 branded drugs with combined annual sales of $100bn will lose intellectual-property protection, reckons Evaluate, a data-provider, putting this at risk from cheap generic alternatives (see chart 1). The equivalent figure averaged $33bn over the past decade. At the same time, finding new cures is getting harder. Jack Scannell, boss of Etheros Pharmaceuticals, a biotech firm, has analysed large drugmakers’ research-and-development (R&D) budgets and regulatory approvals. He finds that in the 1960s $1bn in R&D (at 2008 prices) resulted in ten or so new drug approvals. Today the same $1bn doesn’t get you even one (see chart 2).

Big pharma’s response has been to stick to marketing and distribution, and outsource much of the innovating to the biotechnology sector. In 2023, 57% of all new drugs approved in America originated at small companies, up from 40% eight years earlier. The upstarts are responsible for more than three in four new clinical trials in the early stages and two in three late-stage ones (see chart 3). Kasim Kutay, chief executive of Novo Holdings, which owns a controlling stake in Novo Nordisk and interests in other health-care firms of all sizes, believes that nimbler biotech firms’ singular focus on a particular disease area may give them better odds of success in drug development compared with sprawling big pharma.

Those odds could improve still further thanks to artificial intelligence (AI). Drugmakers have toyed with machine learning for years. BCG, a consultancy, has identified about 200 firms founded in the past decade that use algorithms to find promising molecules. Many have little to show for it. BenevolentAI and Exscientia, two buzzy startups from Britain, recently reported disappointing results from clinical trials for their AI-discovered drugs (to treat eczema and cancer, respectively).

However, recent rapid advances in AI raise hopes that it can make R&D more productive, for real this time. Christoph Meier of BCG predicts a wave of AI-derived drugs. In January Isomorphic Labs, a startup spun off from Google’s AI lab, signed deals with Eli Lilly and Novartis worth nearly $3bn to use its platform to discover small-molecule therapies. In April Xaira, an AI-drug-discovery startup, raised $1bn, one of the largest funding rounds in biotech history. Insilico, another hot AI-based startup, says that its software identified a new drug target and designed a molecule fit for human trials in only 18 months and at a cost of $2.7m.

That is a pittance compared with the billions big pharma spends these days on a portfolio of drugs, only one in ten of which tends to get approved. If AI can reduce the failure rate even by a couple of percentage points, it could have a huge financial impact, says Pratap Khedkar, the boss of ZS, a health-technology consultancy. That would be salutary for the biotech firms, big pharma—and plenty of patients, too. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.