Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

The origins of Home Depot, a big American home-improvement store, are inauspicious. In 1978 two of its co-founders were fired from senior roles at Handy Dan’s, a similar chain in southern California, in a power struggle. They decided to start a rival firm. In an effort to lure in customers on opening day, the co-founders’ children stood outside the doors and handed out dollar bills. “By dinner time they still had plenty of cash,” lamented Bernie Marcus, one of the co-founders, in his autobiography.

Today the company is a giant. Over the past 12 months it racked up $150bn in sales, making it by far America’s biggest home-improvement chain and its third-largest bricks-and-mortar retailer, after Walmart and Costco. The company now employs half a million staff, who profess to “bleed orange”, a reference to the firm’s striking colour scheme. Its market value, at $350bn, exceeds that of Chevron, an oil giant, and Netflix, a streaming darling.

Until about 18 months ago, business was going like a house on fire. A strategy of focusing less on do-it-yourself hobbyists and more on professional contractors, who now account for about half the company’s revenue, had paid off. Those professionals tend to spend more, boosting sales per square foot and improving profitability. With an operating margin of around 15%, the company is more profitable than Lowe’s, a competitor that does less business with tradesmen.

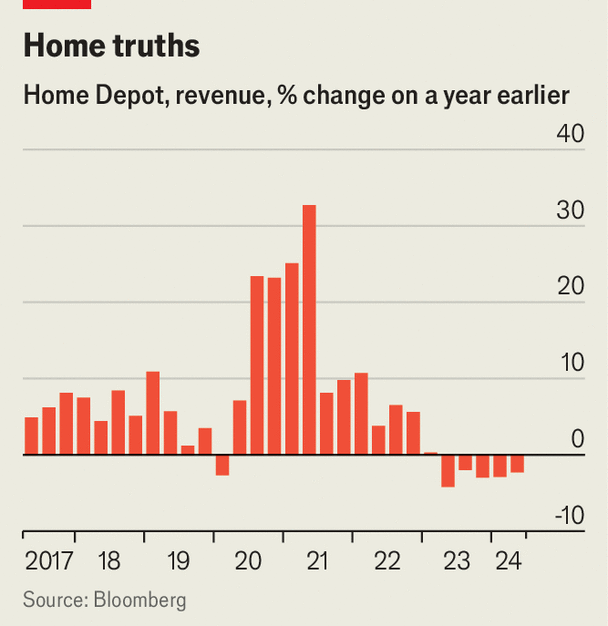

Home Depot’s sales hit the roof during the covid-19 pandemic. The combination of lockdowns and stimulus cheques led to a surge in home renovations. Annual sales growth jumped from an average of 7% between 2017 and 2019 to 17% between 2020 and 2022 (see chart). Past investments by the firm in expanding its supply chain and developing its e-commerce infrastructure proved farsighted. “It was an amazing era,” recalls Richard McPhail, the company’s chief financial officer, “But we knew a period of normalisation was coming.”

On May 14th the company reported that its sales in the quarter to the end of April shrank by 2%, year-on-year, the fifth consecutive decline. Higher mortgage rates have crimped its business by slowing the pace at which people move house. Most renovations happen either when people sell or buy a property. Pet projects, such as remodelling kitchens, which are often paid for with debt, are also being delayed. Home Depot’s value is down by around a fifth since its peak in late 2021. To reduce costs, the company has been sawing back its inventory and reducing its warehouse space, says Mr McPhail.

To boost sales, it is doubling down on its strategy of going after contractors. It plans to target specialists such as plumbers and contractors working on larger projects, including by investing in its ability to deliver materials to sites. It has also been piloting credit schemes for tradesmen. In March the company announced a plan to buy SRS, a trade-distribution company which sells to roofers, pool contractors and landscapers, for $18bn.

That won’t do much to reduce the company’s exposure to the home-improvement market. Home Depot’s business, then, is unlikely to get much of a lift until interest rates start to fall. That should encourage Americans to move home again and unlock demand for improvement projects. Nothing entices people to splash out on renovating their homes quite like cheaper money—apart from, perhaps, being handed dollar bills. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.