Samsung Electronics, South Korea’s most valuable company, is the archetype of vertical integration. The smartphones and other consumer electronics it is best known for accounted for about half of its revenue and a quarter of its operating profit in the period from April to June. The rest came from the components that go into such devices—including the semiconductors that run them.

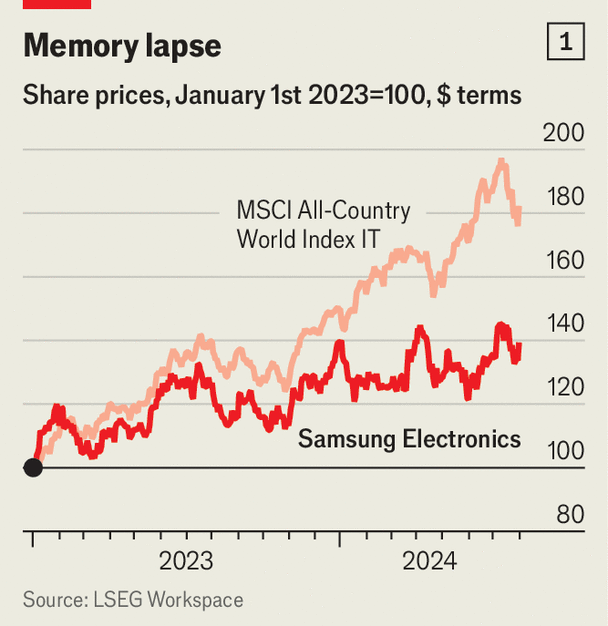

On July 31st the company reported that its operating profit in the most recent quarter was up 16-fold, year on year, thanks to growth in its chip business. Demand is rocketing as tech giants such as Microsoft and Alphabet rush to build data centres to support their artificial-intelligence (AI) ambitions. Samsung’s share price rose 4% on the day. Yet a single bumper quarter cannot obscure the company’s deeper challenges. Most worrying is that it has been losing ground to rival chipmakers. Global technology stocks are up by 82% since the start of 2023. Samsung’s value has risen by just half that (see chart 1).

The South Korean giant is struggling to compete at the cutting-edge of both logic chips (which process information) and memory chips (which store it). In the first category, it has fallen further behind TSMC, a Taiwanese foundry that manufactures semiconductors on behalf of companies such as Nvidia, the leading supplier of AI chips. Between the first quarters of 2019 and 2024 the Taiwanese firm increased its share of the global chip-foundry business from 48% to 61%, according to Trendforce, a research firm. Samsung’s share fell from 19% to 11% (see chart 2).

Samsung’s position as the global leader in memory chips is also under threat. There it is being menaced by SK Hynix, a South Korean firm spun off from Hyundai in 2001 that has become the world’s biggest producer of high-bandwidth memory (HBM) chips. These stack memory chips together, increasing speed and decreasing power consumption, which makes them especially useful in AI applications. In HBM3, the most advanced type currently available, SK Hynix is thought to hold a market share of 90%. Samsung’s memory chips, meanwhile, reportedly suffer from low production yields (the proportion of chips that actually work). Buyers are said to grouse about poor power efficiency.

Because of long lead times for conducting research and building factories, success and failure in the semiconductor industry can be many years, even decades, in the making. For SK Hynix, an early bet on HBM allowed the company to steal a march on its larger competitor. It 2013 it pioneered the original HBM industry standards in collaboration with AMD, an American chip firm. Samsung, by contrast, scaled down its HBM research team in 2019. Industry analysts point to a legacy of complacency among Samsung’s top brass when it comes to shifts in technology.

Samsung’s problems are not limited to its chipmaking business. Its share of global smartphone sales is roughly stable, despite stiffening competition from cheap Chinese rivals. Elsewhere in the supply chain, though, Chinese companies are making life difficult. Two years ago the company gave up on competing against them in the liquid-crystal display (LCD) screen business. It now concentrates on more advanced organic light-emitting diode (OLED) screens, producing them both for its own devices and for those of other companies. Even there, however, it confronts Chinese competition, most notably from BOE Technologies, a state-owned enterprise which has rapidly climbed to prominence in the industry.

Display aggression

In November Samsung filed a complaint against BOE with America’s International Trade Commission, accusing the company of misappropriating its trade secrets (BOE has not responded to the allegation). The OLED market is growing quickly, and South Korean producers such as Samsung still lead at the premium end of it. But the company has reason to be nervous. According to the Korean Display-Industry Association, a trade body, the proportion of Chinese smartphones made with South Korean OLED panels has fallen dramatically, from 78% in 2021 to 16% in 2023.

To make matters worse, the company has lately been grappling with a fractious workforce. In July thousands of its employees gathered outside company facilities south of Seoul, as part of the first organised work stoppage in the firm’s history. The protest over pay and conditions is not yet resolved, and several thousand workers in the company’s semiconductor factory are still refusing to return to work.

Nonetheless, there are glimmers of hope for the company. In July its HBM3 chips were accepted by Nvidia for its H20 processors, which comply with American export rules for the Chinese market. Samsung’s next iteration of HBM chips is now being evaluated by possible buyers. It plans to begin the mass production of cutting-edge two-nanometre logic chips in 2025, and has secured orders from customers including Preferred Networks, a Japanese AI firm. An added advantage for Samsung is that, as a supplier of both memory and logic chips, it can offer a one-stop shop for customers. It already has the necessary capabilities to package chips together, which is tricky.

Buyers of the most advanced memory and logic chips are desperate for more competition in the market. According to Myron Xie of SemiAnalysis, a consultancy, Nvidia is “very keen” that all three of the leading memory-chip companies—Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron, an American firm—are able to offer the products it needs. He adds that, when it comes to manufacturing logic chips, Samsung “doesn’t have to be on par with TSMC, but does need to be closer to make it an acceptable proposition”.

The company is aware of the threats it faces. It has shaken up its leadership, replacing Kyung Kye-hyun, the boss of its chipmaking business, with Jun Young-hyun, who had previously run Samsung’s growing battery subsidiary, in May. And it has been investing to catch up with rivals. Samsung’s capital expenditure over its most recent four quarters amounted to $44bn, compared with $26bn for TSMC and $6bn for SK Hynix (see chart 3). Yet unlike those more focused firms, it is spending to fend off competitors on various fronts. The company’s integrated model has served it well over the decades. But it has its drawbacks, too. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.