Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

From consumer gadgets to cars, China has shown a knack for producing cutting-edge technology. Yet the semiconductors that power the digital economy have proved trickier to master. That has been the source of much anxiety among its political and business elites in recent years. America’s decision in 2022 to halt exports to the country of its whizziest chips and chipmaking tools brought into stark relief the chokehold of China’s geopolitical rivals over the industry. In December last year China’s imports of the lithography machines used to imprint circuits onto silicon wafers surged by 450%, year on year, as local chipmakers raced to buy advanced kit from ASML, the Dutch market leader, before export restrictions by the Netherlands came into effect in January. It has also been hoovering up semiconductor equipment from Japan (see next article).

Although the Chinese government has been splashing subsidies on its domestic chip industry for many years, mounting concern over the trade restrictions being imposed by America and its allies have led it to double down on the effort. In 2022 China’s government ramped up a national drive often referred to as the “Information Innovation” project, or xinchuang, that aims to replace foreign suppliers of, among other things, semiconductor technology. What’s more, whereas the state once pushed reluctant chipmakers to co-operate with local suppliers, their investors and boards now demand it as a form of insurance against trade wars. As a result, China’s semiconductor supply chain is steadily deepening. But can it ever match that of its rivals?

China’s chip industry operates under a shroud of secrecy. Breakthroughs and setbacks are often deemed to be state secrets, the divulgence of which can result in arrest. In August Huawei, a Chinese tech champion, shocked the world by producing a smartphone that contained a seven-nanometre (nm) chip, making it capable of 5G internet speeds. The company is now rumoured to be on the cusp of creating chips as small as 5nm, in partnership with SMIC, China’s largest foundry. Huawei’s Ascend chips, which the firm has designed for AI applications, are reportedly now being used by the likes of Baidu, a local search-engine giant and creator of Ernie, China’s answer to ChatGPT. Like Nvidia, America’s AI-chip champion, Huawei has developed a proprietary software platform, called CANN, that helps developers use its chips to build AI models.

All that still places China’s chip industry far from the technological frontier. Even if Huawei and SMIC eventually succeed at producing 5nm chips, they will remain well behind Samsung, a South Korean tech giant, and TSMC, a Taiwanese foundry, both of which began mass-producing 3nm chips as far back as 2022. China’s lack of advanced lithography equipment will be a big barrier to further progress. In December a top shareholder in SMEE, China’s main hope in lithography, said on social media that the company’s machines had succeeded at producing 28nm chips—though it then quickly deleted the details, causing plenty of confusion. If true, that would still leave the company trailing ASML, whose top-of-the-line machines can produce 3nm chips.

Look away from the bleeding edge, however, and China is steadily chipping away at its reliance on foreign semiconductor technology. Huawei, which was burned in 2019 by sanctions that cut off its access to American technology, has been cultivating China’s wider chipmaking ecosystem. It is reportedly co-operating closely with a number of chip foundries, either by co-investing in projects or exchanging staff. In March last year it declared it had made a number of breakthroughs in the development of electronic-design-automation (EDA) software, used to generate blueprints for chips, which it said would free China’s industry from the need to rely on foreign suppliers of those tools when producing semiconductors of 14nm or more. Though unconfirmed, its collaborator on this is widely believed to be Empyrean, a Chinese maker of EDA tools whose sales have rocketed in recent years.

Such collaborations are happening more often. China’s foundries historically relied on importing tried and tested machinery from abroad. Now some of the largest, including SMIC, have become more open to trialling local alternatives. That gives the suppliers a chance to receive feedback and improve their designs. Although this comes with costs—and risks—for the chipmakers, China’s government is thought to be easing the way by providing subsidies to those of them that purchase local equipment.

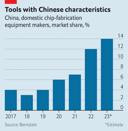

The upshot has been a big boost to Chinese manufacturers of chipmaking equipment. The domestic market share of Chinese producers of wafer-fabrication tools has risen from 4% in 2019 to an estimated 14% last year, according to Bernstein, a broker (see chart). AMEC, a Chinese firm whose machines are used to strip away residual material from a chip, controlled 10% of the Chinese market in 2021. Since then the company has been rapidly gaining share from foreign rivals such as America’s Lam Research (where its founder, Gerald Yin, used to work). Bernstein reckons AMEC’s market share reached 16% last year and will rise to around 30% by 2025. Naura, a peer of AMEC, estimates its sales grew by 50% last year. Wazam, a Chinese supplier of the film used to insulate semiconductors, is beginning to make inroads, too, with a trial under way at a local chipmaker.

Plenty more support will be needed before China can rely entirely on local suppliers for the many stages of chip production. It has already pumped some $150bn of subsidies into its chip industry over the past decade, according to an estimate by America’s Department of Commerce. The government, through its investments, is now present throughout the country’s semiconductor supply chain. SMIC is partially state-owned, as is AMEC. Empyrean is majority-owned by a state enterprise. The government of Shenzhen, the southern city where Huawei is based, holds stakes in many of the chipmakers the company is working with. None of this is as efficient as relying on global supply chains. But China’s officials have security rather than efficiency in mind. And they have decided that the price is worth paying. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.