Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

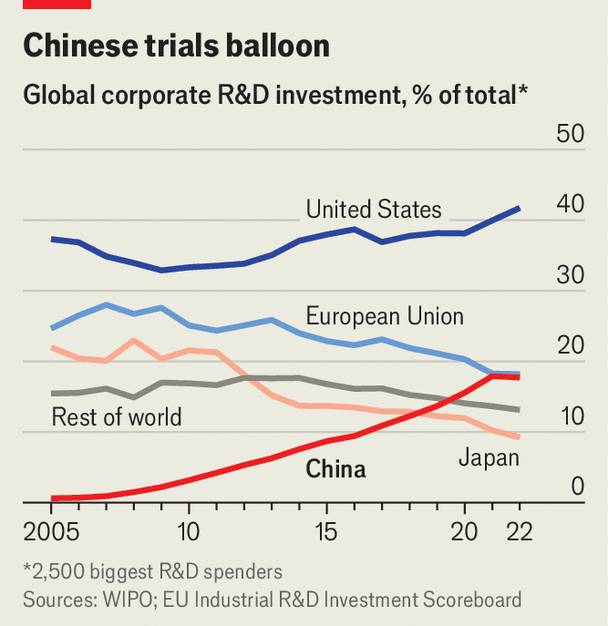

CHINA IS, FAMOUSLY, the world’s factory and a giant market for the world’s companies. More unremarked is its growing role as the world’s research-and-development laboratory. Between 2012 and 2021 foreign firms increased their collective Chinese research personnel by a fifth, to 716,000. Their annual R&D spending in the country almost doubled, to 338bn yuan ($52bn). Add investments by local firms and China now matches Europe’s R&D tally (see chart). Only America splurges more.

In 2022, despite harsh covid-19 lockdowns, 25 new foreign R&D centres opened in Shanghai. Last year, when overall foreign direct investments in China shrivelled by 80%, those in R&D rose by 4%. In the process, Western R&D centres in China have been re-engineered, from places to learn about the domestic market into hotbeds of innovation whose fruits can be found in products sold everywhere.

Foreign chief executives now believe that China’s brainpower and its innovation-curious regulatory regime are crucial ingredients of their companies’ global success. Nowhere else in the world can newfangled technologies, from novel drugs to flying taxis, be tested as quickly as in China, marvels a foreign diplomat. So even as the Chinese economy slows—it grew by a surprisingly tepid 4.7% in the second quarter, year on year—and multinational businesses try to reduce their reliance on Chinese supply chains amid mounting geopolitical tension, global CEOs are desperate to protect this critical third function of their Chinese operations.

Last year Volkswagen invested more than $1bn in an innovation centre in the inland city of Hefei. Bosch, a fellow German firm that supplies parts to Volkswagen and other car giants, is building its own $1bn R&D outpost in nearby Suzhou. HSBC, a British bank, employs thousands of people at an R&D centre in southern China, where they are working on uses of AI, as well as other advanced technology such as blockchains and biometrics.

In February AstraZeneca, a British pharmaceutical company, said it would turn its Shanghai operation into a global R&D hub. In March Apple, maker of the iPhone, unveiled new R&D initiatives around Shenzhen. The next month Bayer, a German drugs-and-chemicals firm, said it was increasing its presence in Shanghai to bring “more technology from China to the world”. In June Tesla, an American electric-vehicle (EV) pioneer, was granted permission by Shanghai’s authorities to conduct tests of its most advanced autonomous-driving systems on the city’s streets.

A big reason for doing lots of R&D in China is the country’s surplus of young engineers and scientists. Southern China is full of small companies developing all manner of clever technologies, from new chemicals to artificial intelligence (AI). This is a giant talent pool in which foreign multinationals can fish.

The Chinese boffins are certainly quite a catch. They are no less talented than their counterparts in the West, where many of them studied and worked, but still command considerably lower pay. The average monthly salary for a newly minted PhD at a foreign company in China is around 13,000 yuan, a third of what they would make in America. One multinational’s China boss reckons he gets 30% more working hours out of his research staff in China than his company manages to coax from similar workers in Europe.

A lot of this work is focused on D rather than R. In many areas China still produces less basic research than America but, by many accounts, more applications. Its app economy is the world’s most sophisticated and, as one AI researcher at a foreign firm in Shanghai explains, leading the world in bringing machine learning to the masses. Cosmetics companies tend to launch more products in China than in other places—and also discontinue more. This lets them test consumers’ reactions more rapidly than in other places, says a marketing specialist. Products which pass the Chinese test can then be offered abroad.

Pharmaceutical companies, among the world’s biggest spenders on R&D, can tap a burgeoning network of world-class contract-research outfits that carry out trials more cheaply than in the West. They have also found that the Chinese are keener to participate in clinical trials than people in other places. China’s population of 1.4bn means that it is also easier to recruit sufficient numbers of patients even for trials of drugs targeting rare diseases, adds Eric Bouteiller of China Europe International Business School.

Trials, whether of cosmetics, apps, medicines or autonomous vehicles, are made simpler by China’s regulatory forbearance. Local governments vie with each other, and with other countries, to be leaders in emerging industries that will undergird what Xi Jinping, China’s president, calls “high-quality growth”.

Pharma executives praise Chinese rules for clinical studies that are independently designed and conducted by researchers rather than drugmakers. In some fields, such as cell therapies for cancer, these investigator-initiated trials in China are identifying successful treatments faster than in other places, says Susan Galbraith of AstraZeneca. Developers of passenger drones are similarly complimentary about rules that allow them to fly their contraptions in designated zones springing up in Chinese cities. Volkswagen began testing a prototype drone in the province of Inner Mongolia in 2022, a world first for a legacy carmaker. Forget San Francisco, says a foreign executive participating in such tests. If you want to set up a testing programme quickly, you had better come to China.

Western companies would understandably hate to be shut out of this R&D paradise. Some are nonetheless bracing for such an eventuality. In June America’s Treasury department issued draft rules that would ban American firms from investing in AI, semiconductors, microelectronics and quantum computing in China. These could come into force later this year.

Lab leaks

At the same time, Mr Xi’s paranoid security apparatus is making it harder to move some intellectual property (ip) generated in China outside its borders, ignoring economically minded officials’ concomitant efforts to attract foreign investment. Exports of some AIs, such as speech- and text-recognition software or even TikTok’s recommendation algorithm, now need permission from the commerce ministry. So far this has not stopped most IP from leaving the country. But this may change at any moment, says Alex Roberts of Linklaters, a law firm. “We are at a tipping point.”

In anticipation of tougher American and Chinese IP regimes, some foreign companies have started to move research staff out of China. Even as Apple doubles down on its Chinese R&D, Microsoft, its big-tech rival, is said to be offering AI researchers in Beijing relocation packages as it winds down more sensitive R&D in China. Although AstraZeneca and Bayer remain ostensibly bullish on Chinese research, some pharmaceutical companies are seeking more clarity about the rules for cross-border transfer of data and IP, says an industry insider, and are rethinking new investments. The flying-taxi firms are staying put for now. One day they, too, may have no choice but to take flight. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.