Most news on China’s manufacturers is bad news for rivals around the world. Foreign governments fear their domestic champions will be pummelled by low-cost Chinese rivals. But on August 5th the world got a small reminder that China’s producers face big problems of their own. Hengchi, an electric-vehicle (EV) maker owned by Evergrande, a failed property developer, told investors that two of its subsidiaries had been forced into bankruptcy. The group originally aimed to sell 1m EVs a year by 2025; amid feverish competition it sold just 1,389 last year.

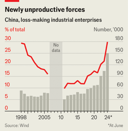

The glut in industrial production is not limited to EVs. About 30% of industrial firms were loss-making at the end of June, rising above the previous recorded peak during the Asian financial crisis in 1998, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (see chart). Its survey of more than 500,000 companies shows a startling deterioration in the conditions for industrial firms in the first half of the year, during which the number of loss-making companies surged by 44%.

In recent years handouts, cheap loans and direct government investment have poured into areas of manufacturing favoured by Xi Jinping, China’s leader, with some remarkable outcomes. On his watch China has become the world leader in EVs and lithium-ion batteries. But its economy is weakening and consumption is sagging. Domestic car sales have fallen in recent months, year on year. Exports in July were below expectations, according to data released on August 7th. Heavily indebted local governments, meanwhile, are also becoming stingier with their support for struggling firms. The Economist has examined three of Mr Xi’s most-favoured industries: EVs, solar modules and semiconductors. The picture that emerges is grim.

Start with EVs. At least eight large makers of the cars have shut down or halted production since the start of 2023. The ripples are visible throughout the supply chain. Qingdao Hi-Tech Moulds, a large auto-parts supplier, warned in a statement earlier this year that the halting of production at HiPhi, an automaker, could send its net profit tumbling by up to 60%. SAIC Anji Logistics, an auto-industry logistics provider, said in recent bankruptcy proceedings that it collapsed mainly because Aiways, another troubled automaker, had failed to pay its bills. The failure of Levdeo, yet another carmaker, has left 4bn yuan ($550m) in unpaid bills to suppliers, agents and banks. Some 52,000 EV-related companies shut down in China last year, an increase of almost 90% on the year before, according to one estimate.

China’s solar industry is also grappling with oversupply. This year the prices of most components of solar modules have fallen below their average production cost. Many companies in the industry are scaling back manufacturing. Others have scrapped plans to enter the market. Haitai Solar, a maker of solar components, has said it expects prices to fall further. The largest producers in the industry have cash reserves that will help them survive. The greatest pressure in solar, as with many other manufacturing industries, is among smaller suppliers that have watched the profits they make from their components disappear, says Alicia García Herrero of Natixis, an investment bank.

A shakeout is occurring in the semiconductor industry, too. Local governments have focused their investments on low-end chip components in an effort to “easily win market share”, notes an industry insider. Those parts are now in great oversupply and many of the companies producing them are failing. In 2023 nearly 11,000 chip-related firms went out of business, roughly 30 a day, according to Qichacha, a company that collects corporate data. It says the figure, which has been reported in Chinese media, is accurate, but that it can no longer supply such numbers as they have become “too sensitive”.

China’s central government has started to recognise the pressure the country’s manufacturers are under. Mr Xi recently acknowledged over-investment in some green technologies. In late July the minutes from a meeting of the politburo, a group of senior government leaders, said that China must avoid “neijuan-style vicious competition”. Neijuan, often translated as “involution”, is a term now commonly used in the country to describe intense, self-harming competition.

Yet it will be difficult for China to avoid a period of industrial involution. Mr Xi’s overriding ambition has been to create high-tech champions across a number of industries that can win in global markets and break his country’s reliance on foreign intellectual property. State support for this has generally flowed through local governments, many of which have spent indiscriminately, resulting in legions of small and uncompetitive suppliers.

Only the strong survive

What is more, the debt local governments have piled up is making it more difficult than in the past for them to rescue troubled industrial firms. Cities and provinces are now 60trn-odd yuan in debt and many have been told to curb spending. Failed investments are only making their fiscal positions worse. The demise of Aikang, a large solar company in Zhejiang province, has become a concern for leaders there. A local-government investment vehicle is its main shareholder.

The state has started to encourage consolidation. But that will not be straightforward. Most companies in sectors with oversupply are looking to trim capacity, not acquire more of it. There will not be many acquisition targets in the solar industry, says Cosimo Ries of Trivium, a consulting firm. It is unlikely the dwindling group of successful EV companies will buy failing brands, which would involve taking responsibility for legacy customers who can no longer get the software updates needed to keep their cars functioning.

In its July meeting, China’s politburo said that the market must filter out weak producers and promote strong ones. In time, that should lead to more capital and labour being allocated to China’s most productive manufacturers, making them mightier still. But it will be painful. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.