Oil has long lubricated the Gulf’s relationships abroad. That is especially so in Asia, which takes in almost three-quarters of its exports of oil and gas. Cheap energy from the Gulf has helped fuel Asia’s rise as the global centre of manufacturing, and filled the sheikhs’ coffers in return.

Now, though, the Gulf’s rulers are eager to diversify their economies away from oil. Muhammad bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s de-facto ruler, wants 50% of his country’s non-oil GDP to come from exports by 2030, up from around 15% last year. He plans to achieve this by building new industries from carmaking and mining to tourism. The United Arab Emirates and other Gulf countries have similarly lofty goals.

For support, the Gulf is turning east. Asian companies are flooding into the region to build infrastructure and set up factories. Meanwhile, the Gulf is investing heavily in Asia to secure access to technologies and profit from the growth of its fast-developing economies. The upshot is a deepening of commercial relationships between the two regions, at the expense of the Gulf’s ties to Western business.

To help transform their economies, the Gulf’s rulers are building vast amounts of infrastructure, from bridges and power plants to desalination systems. Roughly half a trillion dollars’ worth of it is currently under construction across the region, with almost three times as much in planning, according to Emirates NBD, a bank.

That has led to big deals for Asia’s construction giants. Last month China Energy Engineering, a construction firm, won a contract worth $1bn to build a solar plant in Saudi Arabia. In April Samsung E&A and GS Engineering & Construction, two South Korean firms, won deals worth $7bn to build gas plants in the country. Larsen & Toubro, an Indian construction firm, has taken on more than $16bn-worth of work across the Gulf, including for a green-hydrogen plant at NEOM, a futuristic city that Saudi Arabia is erecting in a desert.

A growing number of Asian companies are putting down roots in the Gulf, signalling long-term commitments. Greenfield foreign direct investment from Asia to the Gulf rocketed from $4bn in 2018 to $26bn last year, according to fDi Markets, a data provider (see chart 1). By contrast, investment from America went from around $4bn to just under $7bn in 2023.

Analysts at UNCTAD, an international agency, calculate that over three-quarters of Asia’s greenfield investment in the Gulf last year was for manufacturing facilities, which will produce goods ranging from basic metals to electronics and cars. In July a subsidiary of China Baowu Steel, the world’s largest steelmaker, announced it would double its investment in a new facility in Saudi Arabia, to $1bn. In June Mitsui & Co, a Japanese firm, and GS Energy, a South Korean one, announced they were building an ammonia facility alongside ADNOC, the UAE’s state-owned oil giant. Various Chinese carmakers are building factories in the region. More than money, which the Gulf already has bucketfuls of, Asian companies are offering the region their technical know-how.

Investment is flowing in the other direction, too. The Gulf’s deep-pocketed funds are diversifying away from Western stockmarkets. Last year the Qatar Investment Authority, the country’s sovereign-wealth fund, invested $1bn in Reliance Retail, India’s largest retail chain. The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority is setting up a $4bn fund dedicated to India. Mubadala, another Emirati sovereign-wealth fund, plans to have a quarter of its assets invested in Asia by the end of the decade, double its current share.

Gulf companies are also investing directly in Asia. Baladna, a Qatari agribusiness, intends to set up a $500m dairy facility in the Philippines. ACWA, a Saudi Arabian utility, is building wind and solar projects in Uzbekistan and Indonesia.

Governments on both sides are helping foster deeper commercial ties. The UAE has signed several agreements with Asian countries, including one with South Korea in May, that have lowered trade barriers. Bilateral meetings such as the Dubai Business Forum that took place in Beijing last month have become a way to seal commercial deals with the support of government officials. Some policymakers now speak of expanding Asia’s regional trade agreements to include the six-member Gulf Cooperation Council.

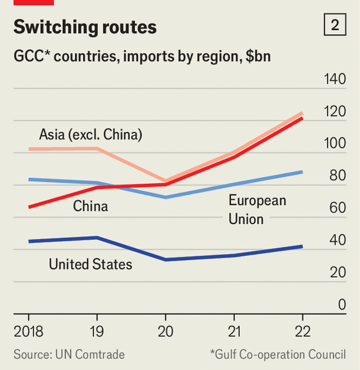

At the same time, the Gulf’s economic relationship with the West is shifting. Trade ties are loosening: America and the six largest economies in the EU last year consumed only 8% of its exports, down from 27% in 1990, according to Efstathios Polyzos of Zayed University and Emilie Rutledge of the Open University. Between 2018 and 2022 Gulf imports from America and the EU rose from $128bn to $130bn; imports from Asia soared from $169bn to $247bn (see chart 2).

Although recent flows have moderated, Western companies still retain a sizeable stock of investment in the Gulf. (Exxon, an American oil giant, began drilling in Abu Dhabi in 1950, two decades before the UAE was established.) Much of that investment is skewed towards hydrocarbons, although some spending from non-energy firms is trickling in. Earlier this year AWS, Amazon’s cloud business, said it would invest $5bn in Saudi Arabia.

America is therefore keeping a keen eye on China’s rapidly growing commercial presence in the region. Treasury officials have been monitoring business dealings there, particularly those in high-tech industries. An investment by Microsoft in G42, an artificial-intelligence startup, earlier this year came with the stipulation that the Emirati firm sever its ties with Huawei, a Chinese tech giant. The American government was reported to be closely involved in the negotiations.

Officials in the Gulf lament that, with American investment volatile, they have little choice but to look elsewhere. As the Gulf keeps diversifying, expect to see more geopolitical machinations playing out. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.