Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

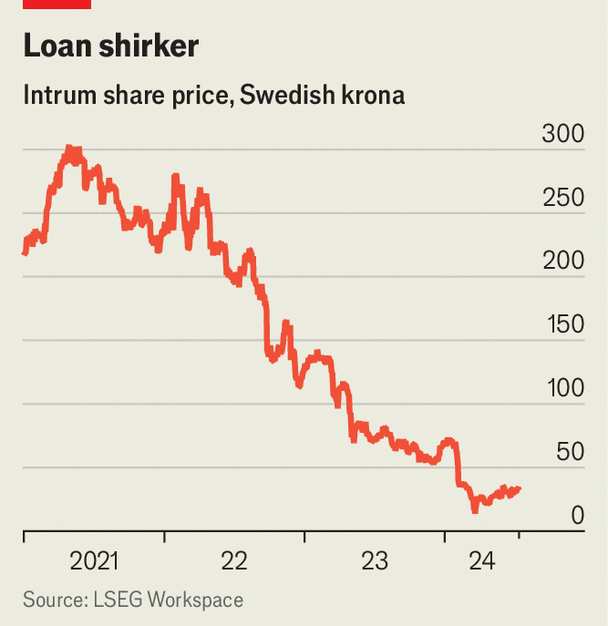

Behind every on-screen loan shark is an even harder character making sure the mob’s debts are paid—make Peter pay, or Paulie might break your legs. The financial system is less violent, but similarly interconnected. Intrum, Europe’s biggest debt collector, has struggled to make its business of buying and settling bad loans work. Now it is under pressure from its own excessive borrowing. The firm’s $6bn pile of debt trades at levels indicating deep distress. So do its shares, whose value has fallen by half this year (see chart).

On July 11th Intrum said it had reached an agreement with its creditors. Most bondholders will take a 10% haircut in exchange for new shares in the company, which looks like a cross between a call centre and a hedge fund. It earns around half its revenue collecting non-performing loans (NPLs) on behalf of other firms—this involves hassling errant borrowers with letters and telephone calls. The second, more troublesome part of Intrum’s business entails not just chasing loans but actually owning them.

After the euro-zone crisis of the early 2010s, banks looking to shed their NPLs found an eager buyer in Intrum, which borrowed heavily to fund its expansion. Its model has proved unsustainable. The share of bad loans on banks’ balance-sheets has fallen to less than 2%, from 7.5% in 2015, according to the European Central Bank. Lenders are offloading fewer bargains as a result. Higher interest rates, meanwhile, have increased Intrum’s cost of capital. “They are being squeezed from both sides,” says Angeliki Bairaktari of JPMorgan Chase, a bank.

Others are facing a crunch, too. IQera, an indebted French debt-collector, has a balance-sheet in need of surgery. So does Lowell, a British one. But not all of Intrum’s woes can be blamed on its industry’s business model. Merging with Lindorff, a competitor backed by private equity, left the firm saddled with debt in 2017. When Intrum’s new chief financial officer joins this year, he will be the eighth person to warm that chair since 2018.

Intrum must now reduce its debt further. In January it announced a deal to offload a portfolio of NPLs to Cerberus, an American investment firm, and for months it has been negotiating with its creditors, including sharp-elbowed investors that, like Intrum, specialise in wringing value from bad debts. Under its plan, most of Intrum’s lenders will suffer a modest haircut and Intrum will start paying them back only in 2027.

Investment funds are probably a better home for NPLs than highly leveraged corporate balance-sheets. Intrum wants to strike more deals like the one with Cerberus—shedding much of the risk of investing in NPLs while continuing to earn fees from sourcing and collecting them. And though the European economy’s decent health means fewer NPLs, it reckons technology will boost the efficiency of its collections. If it fails, creditors will come knocking. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.