Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

FOR YEARS ExxonMobil was the top dog among the world’s private-sector oil companies. It was the biggest of the Western majors, and the best-managed. It regularly posted higher returns on capital than its peers and enjoyed superior stockmarket valuations. This led to an arrogance among its chief executives that infuriated not just greens but even other oilmen. In 2003 Lee Raymond, a former boss with a ferocious temper, bragged that “everyone at this company works for the general good—and I’m the general of that general good.”

More recently ExxonMobil appeared to have lost some of this braggadocio. Between 2016 and 2020, together with the rest of the industry, it eked out meagre returns as oil prices languished. At the same time it was hounded by climate activists and asset managers concerned about environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. The lowest point came three years ago when it suffered an unprecedented defeat at the hands of Engine No.1, an obscure activist fund that managed to get three climate-minded directors elected to its board.

With profits resurgent on the back of two years of buoyant oil prices, the bad boy of big oil is back. In October it launched a $60bn takeover of Pioneer, an independent shale-oil producer. Later it claimed a contractual right of first refusal to a lucrative concession in Guyana held by Hess, a smaller oil firm. That claim, currently in arbitration at a court in Paris, could derail the $53bn acquisition of Hess by Chevron, ExxonMobil’s main American rival. Darren Woods, the current chief executive, is once again infuriating climate campaigners and ESG investors by criticising global efforts to eliminate fossil fuels as unrealistic, even foolhardy. And on May 29th the company’s management got its full slate of directors approved at this year’s annual shareholder meeting—ESG objections from critics notwithstanding.

Yet Mr Woods’s brashest recent move concerns another shareholder fracas. In December Arjuna Capital, an American activist fund, and Follow This, a European one, each with a tiny stake in ExxonMobil, submitted a proposal to expand the company’s emissions-reductions efforts by including targets to limit indirect emissions from the supply chain and the end use of its hydrocarbons. ExxonMobil has roundly rejected such ideas as somewhere between impractical and suicidal. It argues that the two funds’ latest proposal sought not to create shareholder value but rather to make the company “shrink”. Similar efforts made by the duo at previous annual meetings have flopped, receiving 27% support in 2022 and barely 10% last year. Yet rather than let them fail once again, Mr Woods has taken the unusual step of suing the two small shareholders.

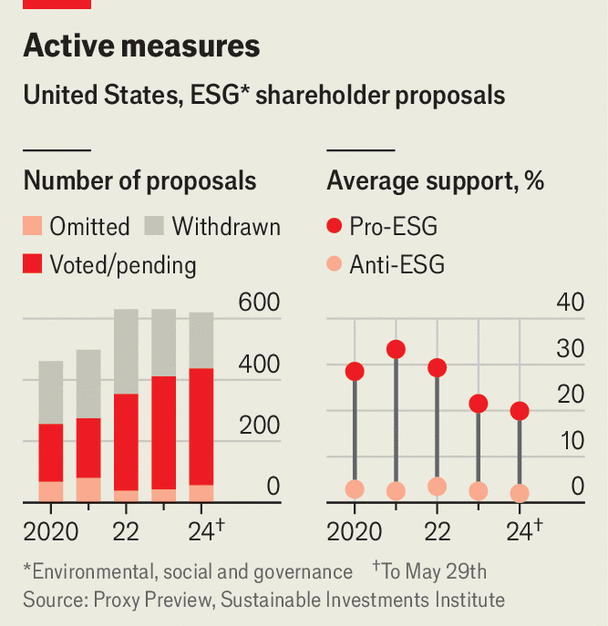

Many large companies, in the energy industry and beyond, are contending with a spate of ESG campaigns (see chart). Many of these proxy proposals are ill-founded and impractical, promoted by gadflies with token shareholdings. Bosses typically deal with such nuisance petitions by appealing to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), America’s markets regulator. Historically, the SEC let companies know (through something known as a “no action” letter) that they were not required to allow a troublesome motion to reach a vote at the annual meeting. The problem, in the eyes of ExxonMobil, is that the proxy process “has become ripe for abuse” and the way the SEC goes about excluding frivolous proposals is “flawed”.

Self-serving, perhaps. But Mr Woods is not alone in this view. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, has also argued that the SEC’s pro-ESG stance has led to lower-quality and more politicised shareholder resolutions. Robert Eccles, an ESG scholar at Oxford University’s Said Business School, rejects as hysteria the claim from some progressives that the oil giant is trying to crush small shareholders. In his view, “Exxon is really after the SEC’s broken regulatory review process.”

Mr Woods’s decision in January to bypass the SEC entirely and instead take Arjuna and Follow This to court won plaudits from those fed up with pesky ESG activists. Tom Quaadman of the US Chamber of Commerce, which filed a court brief in support of the oil company’s case, brands actions like those taken by Arjuna and Follow This as “the tyranny of the minority”.

Corporate-governance types are less complimentary about ExxonMobil’s hardball tactics. Mary-Hunter McDonnell of the Wharton School adds that denying shareholders access to corporate proxies that the regulator has deemed legitimate is “just bad governance”. Charles Elson of the University of Delaware, who has served on many corporate boards, thinks that the company erred in bringing litigation against its owners, however small. ”You don’t bite the hand that feeds you,” he cautions. Such criticisms mounted when ExxonMobil did not drop its lawsuit even after the two activists were browbeaten into withdrawing their proposal.

It is unclear why ExxonMobil decided to fight the two investors tooth and nail. One conservative scholar close to the oil industry thinks it may have had more to do with shoring up political support on America’s right, to which ESG is a red rag, than with actual concerns about the SEC’s revised approach to corporate governance.

Whatever the reason, the firm’s heavy-handed tactics have led several large investors to express displeasure with its conduct. Norway’s $1.6trn sovereign-wealth fund voted against ExxonMobil’s nominee for lead independent director. CalPERS, which manages California’s public-sector pensions, rejected its entire slate, including Mr Woods. That its directors nonetheless won, on average, 95% of the proxy vote must leave ExxonMobil feeling vindicated—and further emboldened. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.