Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

Lululemon, a CANADIAN maker of yoga outfits, does not have many things in common with Rolls-Royce, a British engine manufacturer. One thing they do share, along with scores of other foreign companies, is space in the sprawling Embassy Manyata Business Park in Bangalore. Hundreds of others, among them Maersk, a Danish shipping firm, Samsung, a South Korean electronics giant, and Wells Fargo, an American bank, have offices within a few miles. Many more of these white-collar outposts can be found in cities including Chennai, Pune and Hyderabad.

Back in the 1990s global firms such as General Electric, a once-mighty conglomerate, began to rely on Indian workers to perform tedious tasks such as filling in forms and patching software for mainframe computers. Over time much of that drudgery was absorbed by Indian outsourcers such as Infosys, TCS and Wipro. Now foreign firms have begun to think bigger about the types of white-collar jobs that can be done by India’s cheap but well-educated workers. Many have set up “global capability centres” (GCCs) to offshore tasks from data analysis to research and development (R&D), helping fuel a new wave of services-led growth for India.

It has long been easier to offshore white-collar work to India than the blue-collar variety. Spreadsheets and emails do not need to travel along the country’s congested roads or otherwise rely on its shoddy infrastructure. (GCCs generally have dependable internet connections, a luxury not always enjoyed in India.) Labour laws covering matters such as redundancies and—crucially for global firms—working hours are less restrictive for the country’s white-collar workers, too.

More recently, technologies such as cloud computing and video conferencing have made it less cumbersome to tap India’s vast pool of brainy workers. Having learned how to supervise employees remotely through the covid-19 pandemic, plenty of bosses will have now pondered whether some roles could be done from farther afield.

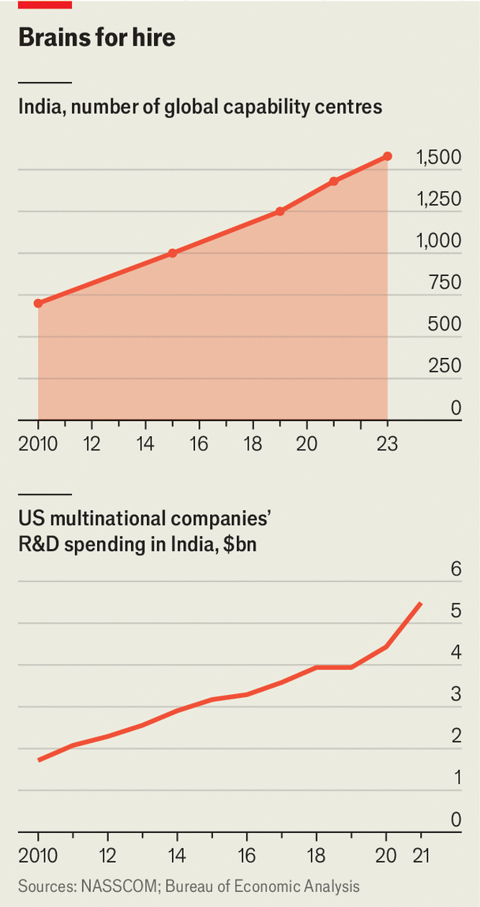

All that helps explain why the number of GCCs operating in India has ballooned from 700 in 2010 to 1,580 last year, according to NASSCOM, an industry body (see chart). A new centre now opens roughly every week, two-fifths of them in and around Bangalore. India’s GCCs generated a combined $46bn in revenues last year, estimates NASSCOM.

Even that may vastly understate their activity. Many multinational companies do not share the financial details of their GCCs, which means calculating their economic contribution involves a good deal of guesswork. Wizmatic, a consultancy based in Pune, thinks the revenues of Indian GCCs could be as high as $120bn, a sum equal to roughly 3.5% of the country’s GDP.

These outposts employ some 3.2m workers, reckons Wizmatic. Many Indian graduates jump at the opportunity to work at one. Students hired by the country’s outsourcing giants typically earn less than $10,000 a year. Moving to a GCC can triple that. Most foreign firms setting up these offices also plump for premium buildings with cafés and other amenities. Lululemon provides its Indian workers with a space, and time, for exercise, an uncommon perk in Indian workplaces.

The activities of GCCs are increasingly varied. Lululemon’s workers in India pore over sales data and tell branches in Dubai to stock more bright yellows, pinks and greens, and ones in New York to stock more blacks and greys. Although design is done in Canada, the company’s GCC is involved in everything from setting prices to managing supply chains. Wells Fargo’s teams in Bangalore, Chennai and Hyderabad support the bank’s operations in areas ranging from lending to managing investment portfolios.

More than 85 foreign semiconductor companies, including Intel and Nvidia, now conduct design work in Bangalore. Tech giants such as Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft also have R&D centres in the city, as do Boeing, an aircraft manufacturer, and Walmart, a retail giant. Mercedes-Benz, a German carmaker, employs nearly 6,000 workers at its R&D centre in Bangalore, its largest such operation outside Germany. Over the past four years its team in India has produced 32 patents.

In 2010 American multinationals spent $1.7bn on R&D activities in India, according to America’s Bureau of Economic Analysis. By 2021, the latest year available, that figure had surged to $5.5bn. Growing geopolitical tension with the West means that China, India’s principal rival hub for low-cost R&D, has lost some of its appeal. On May 16th it was reported that Microsoft had asked hundreds of employees working on advanced technologies such as machine learning and cloud computing in the country to relocate.

All this has helped turbocharge India’s services exports, which hit $338bn last year, or nearly 10% of GDP, up from $53bn in 2005, reckons Goldman Sachs, a bank. The country now accounts for 4.6% of global services exports, up from roughly 2% in 2005. India’s goods exports, by contrast, account for just 1.8% of the global total, up from 1% in 2005.

India’s government has been busily trying to tilt that balance towards manufacturing, by modernising the country’s infrastructure and doling out subsidies to foreign firms that produce there. Plenty of other countries are vying to steal China’s title as the world’s factory. None, however, has as good a shot as India at becoming the world’s office. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.