Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

With sound-stage doors made big enough for performing elephants, the century-old Paramount Pictures lot on Melrose Avenue is a living museum of the film business. Now the studio, one of the world’s first—and the last still based in central Hollywood—is for sale. Paramount’s controlling shareholder, Shari Redstone, is seeking a buyer for the teetering empire she inherited from her father Sumner, who died in 2020. For six months suitors have come and gone. On July 2nd it was reported that David Ellison, a tech heir whose previous bid for Paramount was rebuffed only in June, had reached a preliminary agreement to buy Ms Redstone’s stake in the company.

The turbulent picture at Paramount reflects the state of Hollywood. Show business has entered an age of austerity. Cinema is suffering from long covid; this year’s domestic box-office takings are forecast to be 30% lower than in 2019. Cable subscriptions are falling faster than ever, with a record 2.4m Americans cancelling their pay-TV in the latest quarter.

Streaming, the lifeboat that was supposed to rescue entertainment companies from these sinking legacy businesses, is still a money-loser for everyone except Netflix. In the past two years subscriptions have levelled off at about four per household in America. Netflix, with 270m subscribers worldwide, is reliably among them in most homes. Disney, which has clocked over 200m subscriptions (and expects to make a profit on streaming in the third quarter of this year), also looks safe. Amazon gives its video service away to 300m Prime subscribers around the world and is not going anywhere. Apple, likewise, can afford to sink money into its TV+ service for as long as it likes.

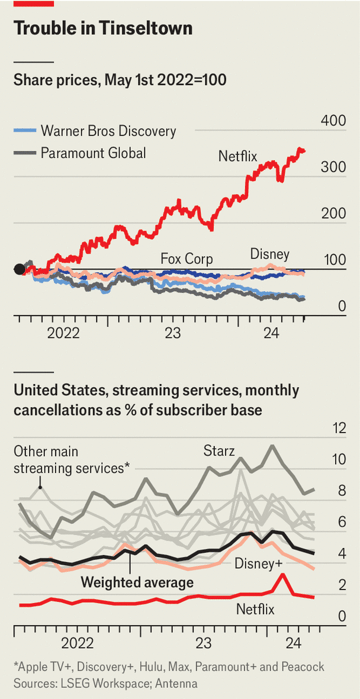

The rest are fighting a losing battle for attention. In the past two years some studios have shed more than half of their market value (see chart). “There are a lot of players. There are a lot of players that are losing a lot of money,” David Zaslav, head of Warner Bros Discovery (WBD), another troubled studio, summed up in May. The way to survive, Mr Zaslav intimated, was for studios that once bitterly competed to come together. “M&A fervour is in the air in Hollywood,” says Robert Fishman of MoffettNathanson, a firm of analysts. The result is that, like a bad movie in post-production, the industry is being trimmed and edited back together. Will the result be any more watchable?

There is certainly lots of action. In recent months Paramount held fruitless merger talks with Comcast, a cable giant which owns NBCUniversal, as well as with WBD and Sony. In June Paramount was on the verge of selling to Mr Ellison, who runs Skydance Media, a production company, only for Ms Redstone to pull out at the last minute. The deal is now said to be back on because Skydance improved its offer. Until Paramount’s future is settled, other deals are up in the air. “People are dying for Paramount to get its mojo back,” says one frustrated executive at a rival studio.

Another company in need of more heft is WBD, itself the result of a merger two years ago. Its Max streaming service is stuffed with Emmy-bait, from “Succession” to the expanding “Game of Thrones” universe. But it lacks scale and is thought to be losing money on streaming (the firm does not break out the numbers). Since the second anniversary of its formation in April, it has been free to buy or sell assets without being clobbered by tax penalties. Jason Kilar, former head of Warner, said recently that he did not expect it to be a standalone business in 18 months’ time.

One possible partner for WBD is another subscale streamer, NBCUniversal’s Peacock. Some observers wonder if WBD could do a deal with Fox, which sold its 21st Century studio to Disney in 2019 but retains television interests, including a quietly successful streamer called Tubi (which expanded into Britain on July 2nd). Fox is undervalued relative to its asset mix, which includes a studio lot in Century City, argues Mr Fishman. The great unknown is what its 93-year-old controlling shareholder, Rupert Murdoch, and his heirs, want to do with Fox, particularly its fiery news operation.

That may become clearer after America’s presidential election in November. The potential return of Donald Trump, who leads in most polls, complicates the regulatory picture. His unpredictable administration waved through Disney’s $71bn acquisition of 21st Century Fox. But it tried (unsuccessfully) to stop AT&T buying Time Warner, a move which many attributed to Mr Trump’s dislike of Warner’s CNN news channel. A second Trump presidency could make it hard for Comcast to do big deals: the company owns the MSNBC news network, which Mr Trump despises as much as CNN.

In the meantime, entertainment companies are finding other ways to team up. Disney, WBD and Fox will launch a sport-focused streaming service, Venu Sports (pronounced “venue”), in the autumn, if regulators allow it. Paramount’s leaders told staff on June 25th that they were in talks with potential streaming partners “that will significantly transform the scale and economics of the service” internationally. Paramount and NBCUniversal already run a streaming joint venture in Europe called SkyShowtime.

Former rivals are also packaging their services. Disney and WBD unveiled a discounted bundle of their streamers in May. Weeks later Comcast launched a “StreamSaver” bundle for its broadband customers, rolling Netflix, Peacock and Apple TV+ together. The aim is to reduce customer churn, a problem stalking Hollywood. Streamers lose about 5% of their American subscribers every month, according to Antenna, a data company. This leaves them replacing more than half their customers each year—something that the older studios are not used to, having previously dealt with cable companies, which handled customer acquisition.

Bundles make for “healthier subs”, one executive says: more content means less quitting. Antenna calculates that last year monthly churn among subscribers to Disney’s entertainment-and-sport bundle was 3-4%, versus 5% or so among those who get only Disney+.

Perhaps the starkest example of the grudging new co-operation is the return of licensing. In the early days of streaming studios kept their content to themselves. Bob Iger, Disney’s boss, compared licensing Disney shows to Netflix to “selling nuclear-weapons technology to a third-world country”. Now, as studios strive to improve their cash flow, the arms trade is back in business. Disney titles such as “Lost” and “Home Improvement” are on Netflix.

Play-it-again sums

WBD is renting out its back catalogue, too, including shows like “Sex and the City” and “Young Sheldon”. Paramount said in June that it was exploring more licensing. The ability to raid rivals’ archives is allowing big spenders like Netflix to rely less on original production. Acquired content made up nearly half of viewing on Netflix in the second half of 2023, including 11 of its 20 most-watched series, according to MoffettNathanson.

With subscribers increasingly being steered towards big bundles of content, streaming is “just cable over the internet now”, concludes an executive. That is an exaggeration: it is still much easier for viewers to flit between subscriptions, which is why the profits even at Netflix are nowhere near those of the cable era.

Still, the consumer bonanza of a few years ago is over. Prices are rising (Disney+ costs twice what it did at its launch in 2019), commercials are creeping in, content budgets are tightening and competition is turning to co-operation. As show business shifts its focus from boosting growth to breaking even, the new Hollywood will look a little better for shareholders—but less fun for audiences. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.