Few companies have gained as much value with as little fanfare as Broadcom has in recent years. Since the end of 2022 the American chipmaker’s market capitalisation has rocketed from around $230bn to more than $700bn. It is now the world’s 11th-most valuable company and its third-most valuable chipmaker, behind only Nvidia, the leader in artificial-intelligence (AI) semiconductors, and TSMC, the biggest manufacturer of them.

Like Nvidia and TSMC, Broadcom has profited richly from the AI frenzy. Tech giants such as Google, Amazon and Microsoft rely heavily on Nvidia’s processors to run their AI models, but they have also been developing their own custom chips, and have turned to Broadcom for help. A recently released version of Google’s AI chip was developed by Broadcom. OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, is reportedly exploring designing a custom chip with the company’s assistance. Broadcom has also benefited from its position as one of the leading suppliers of networking chips for data centres and its ownership of VMware, which makes software for in-house “private clouds”. Demand for both has rocketed amid the AI mania.

The upshot has been a surge in sales and profits. Analysts reckon that in the quarter ending in August Broadcom’s revenue grew by 47% and its operating profit by 39%, year on year; the company will report its results on September 5th, after The Economist goes to press.

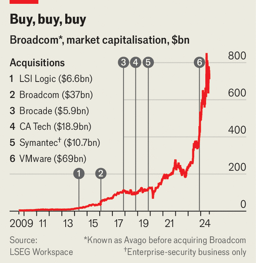

As jittery investors begin to wonder how long the AI boom can last, they would do well to remember that Broadcom’s rise began well before the coming of ChatGPT. In the decade preceding the chatbot’s release Broadcom’s value increased 20-fold (see chart). More than whizzy technologies, it is dealmaking that has fuelled the company’s growth; since its founding in 2005 the firm has spent more than $140bn on acquisitions. More than a tech firm, Broadcom is a buy-out shop.

Broadcom began life in 2005 as Avago, a spin-off from Agilent Technologies, a manufacturer of electrical components, that itself was carved out of Hewlett-Packard in 1999. In 2015, after acquiring a string of smaller semiconductor firms, Avago struck a deal to devour Broadcom, a chip designer with revenues that were nearly double its own, for $37bn—and then took the bigger company’s name.

Soon Broadcom ran out of big chipmakers that it could buy without ruffling trustbusters’ feathers. Its attempted takeover of Qualcomm, a maker of smartphone chips, for $130bn was quashed by Donald Trump, then America’s president, in 2018 on national-security grounds. (At the time Broadcom was based in Singapore.) The company thus turned to software instead, which now accounts for about a fifth of its revenue. After gobbling up a a maker of software for mainframe computers and a cyber-security business, it made its largest-ever acquisition last year, when it forked over $69bn for VMware.

The result today is a sprawling portfolio of loosely related businesses (Broadcom’s motto, fittingly, is “Connecting Everything”). Yet there is a logic to the company’s dealmaking. In choosing its targets, Broadcom looks for firms that have good products and a dominant market share but are poorly run. Its private-equity-style playbook involves slashing costs by eliminating layers of management and focusing on a reduced number of products. In November, shortly after it completed its acquisition of VMware, Broadcom fired 2,800 employees. Price hikes and bundling are common, too, as many of VMware’s customers are now discovering.

That is not to say Broadcom focuses entirely on short-term gains. Sales and marketing departments may be cut down after an acquisition, but investment in research and development is often increased, notes Dan Nishball of SemiAnalysis, a consultancy. Engineers make up almost three-quarters of Broadcom’s workforce. Hock Tan, the company’s long-time boss, has argued that fewer non-engineers at a tech firm helps “keep it simple”.

Plenty could yet go wrong for Broadcom. Although it is less dependent on AI than Nvidia, a slowdown in spending on the technology would be painful. Its customers, including Apple and Google, are also ramping up their own chip design efforts, which could undermine its lucrative business for custom silicon. Designing AI chips is tricky, notes Mark Lipacis of Evercore, an investment bank; it will take time for Broadcom’s customers to develop the necessary know-how. But other challengers could still crop up. It is rumoured that Nvidia may soon start designing chips for some of its larger customers.

An even bigger worry may be succession. Mr Tan, who is in his 70s, has run the company since 2006. Broadcom’s boss has been rewarded handsomely for his efforts; he was the highest-paid chief executive of any company in America’s S&P 500 index last year, with a package worth $162m. Finding a successor with both technical expertise and Mr Tan’s knack for dealmaking will be tough. For now he has said he plans to be at the helm for at least the next four years. Mr Tan may have a few more deals left in him yet. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.