Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

To witness India’s growing role as a manufacturing hub, dodge Bangalore’s notorious traffic and head north. Around 45km outside the city, amid the dust and debris of construction, Foxconn, a Taiwanese contract manufacturer, is turning 120 hectares of farmland into a factory that will produce around 20m iPhones a year. Foxconn’s plant will be the third facility near Bangalore dedicated to churning out phones for Apple, an American tech giant. The other two are run by Tata, India’s largest conglomerate.

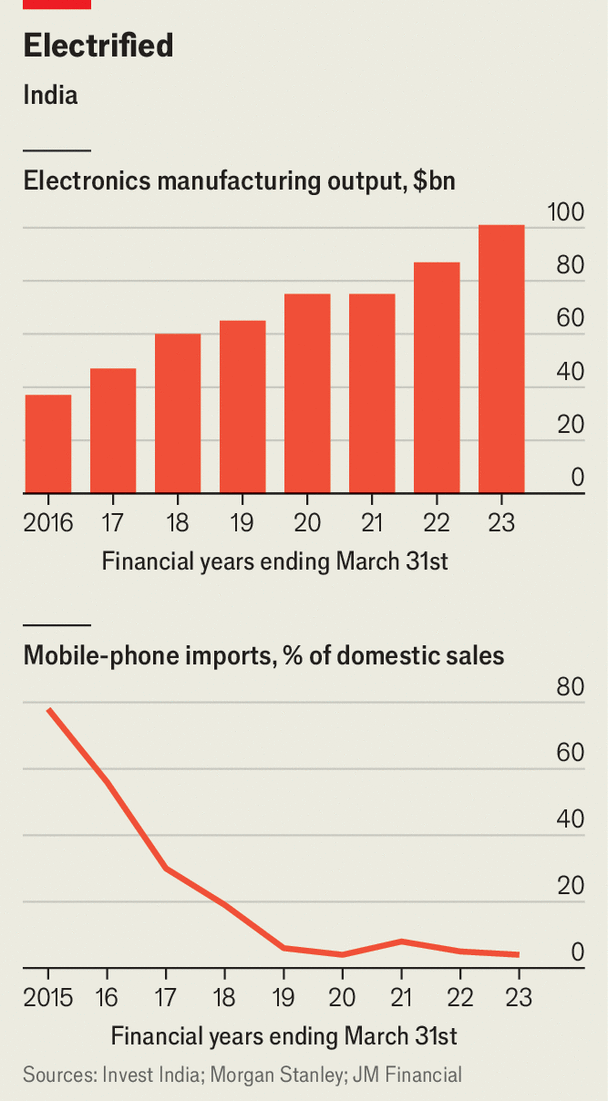

Bangalore, home to many of India’s IT giants, is better known for its software than its hardware. However, the new factories suggest that, in one industry at least, India’s efforts to transform itself into a manufacturing powerhouse are bearing fruit. Electronics manufacturing—the business of building mobile phones, televisions and other gadgets—is thriving in India. The value of electronics it produced rose from $37bn to $105bn (3% of GDP) between the fiscal years ending in March 2016 and March 2023 (see chart). The government wants to triple this again by fiscal 2026. Although India’s production of electronics accounts for just 3% of the global total, its share is growing faster than any other country’s.

Nowhere is this boom more evident than in the production of phones, which makes up nearly half of India’s electronics industry. The country is the world’s second-largest maker of the devices, trailing only China. In fiscal 2015 India imported almost four-fifths of its phones. It now imports barely any. Apple sources about one in seven of its iPhones from India, double what it did a year ago. Samsung, a South Korean rival, has its largest phone-making facility in the country.

Contract manufacturers, which build products on behalf of other companies, have been rapidly expanding in India. Foxconn, which assembles nearly two-thirds of Indian-made iPhones, now has more than 30 Indian factories and employs 40,000 Indian workers. Although its Indian operations account for less than 5% of its total revenue, the company is steadily increasing its investments. It has set aside $2.6bn for its Bangalore factory. Last year Liu Young, Foxconn’s boss, told investors that the several billion dollars it had invested in India so far was “only the beginning”. A steady stream of foreign suppliers to Foxconn and its peers have also set up shop in India. PwC, an advisory firm, estimates that the share of value India added to phones produced in the country increased from 2% in 2014 to 15% in 2022.

It is not only foreign firms that have piled in. Tata first entered phone-making in 2021 by building parts for older models of the iPhone. After initial issues with quality control, the company has found its footing. In November it acquired the Indian operations of Wistron, a Taiwanese firm, and began assembling iPhones. Tata now plans to expand its factories to nab a larger share of business with Apple.

Another Indian company benefiting from the device-making bonanza is Dixon Technologies, India’s largest domestic electronics manufacturer. The company, which began making gadgets for the local market three decades ago, has jumped into producing smartphones for foreign companies. It now employs 27,000 people, up from 2,000 a decade ago. Over the past year its share price has risen by 150%.

India’s electronics boom reflects a combination of the desire of Western tech firms such as Apple to reduce their reliance on China and the vast appetite of India’s 1.4bn people for whizzy devices such as smartphones. Generous handouts from the government have sweetened the deal for companies mulling production in India. In 2020 the government announced a programme of “production-linked incentives” for manufacturers in various industries, including electronics.

Sunil Vachani, Dixon’s boss, credits the government for its belief in India’s manufacturing potential, which he says has brought about “a change in the mindset” of the country. India’s government has certainly been busy wooing foreign manufacturers. In January it awarded the Padma Bhushan, the country’s third-highest civilian award, to Mr Liu of Foxconn. Pranay Kotasthane of the Takshashila Institution, a think-tank in Bangalore, says the government has been courting companies such as Foxconn to lure in “anchor investors” around which supply chains can form.

The hope is that India will one day be able to dislodge China as the world’s electronics factory. Narendra Modi’s electoral setback earlier this month, in which the prime minister lost his parliamentary majority, does not appear to have dampened enthusiasm for that goal. His new government has signalled continuity in its support for manufacturing.

India’s progress certainly looks promising. In the 12 months to the end of March, its electronic exports reached $29bn, up by 24%, year on year. Still, that is a far cry from the almost $900bn of electronics China exported last year. There is, then, plenty more to do. Naushad Forbes, an Indian businessman, argues that unless Indian firms invest in deepening their technical know-how, they will struggle to compete in more advanced areas like chipmaking. India’s reluctance to lower trade barriers with its Asian neighbours is also a hindrance. Import duties for the raw materials and components needed to produce electronics are typically higher than in other countries that are vying to steal production away from China, such as Vietnam.

For his part, Mr Vachani of Dixon is bullish. He believes that “this a Y2K moment” for India’s electronic manufacturing, a reference to the panic over a computer bug at the turn of the century that put the wind in the sails of India’s IT industry. Perhaps, in time, the term “Bangalored” could refer not, as today, to the draining of white-collar jobs away from America, but of blue-collar ones from China. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.