Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

In recent years Paris has undergone an astonishing revival. Global businessmen, financiers and techies casually drop into conversation that they are spending more time in the City of Light. Wall Street banks have expanded their offices there; venture capitalists are signing more cheques for French startups. An annual investment summit, held in May at the nearby Palace of Versailles, has become a fixture in chief executives’ calendars. This year, as they sipped champagne with France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, company bosses pledged investment projects worth €15bn ($16bn).

The renaissance is part of Mr Macron’s grand ambition to make France more innovative and business-friendly. But that project is now in danger.

After his centrist party suffered a drubbing in the elections to the European Parliament, the president called a snap national parliamentary vote, the first round of which is due to be held on June 30th. Hard-right and hard-left parties are polling well ahead of Mr Macron’s group. Both have unsustainable spending plans that are spooking investors. Neither is especially friendly to international business.

Only a few weeks ago Paris, which is also due to host the 2024 Summer Olympics in July, was basking in the limelight. Now a cloud of uncertainty hangs over its great commercial revival.

The French capital was once seen as a city of red tape, high taxes and clogged-up streets, which dimmed its appeal to anyone other than tourists. But over the seven years that Mr Macron, a former investment banker, has been in charge, much has changed. That is most evident in two areas: finance and tech.

Over the past decade Paris has been climbing the rankings of the world’s financial centres (see chart 1). French financiers manage €5trn in assets, up from €3.8trn in 2015. Amundi, a French firm that has become Europe’s biggest fund manager, looks after €2.1trn-worth, more than double the figure a decade ago.

Wall Street has been increasing its Parisian presence. In 2021 JPMorgan Chase, America’s biggest bank, inaugurated Paris as its main European trading floor, where it now employs around 1,000 people. Bank of America has increased its Parisian headcount ten-fold, to 700; Citigroup’s has risen from 170 to 400, with space in its office for 200 more. Morgan Stanley has more than doubled its headcount in Paris over the past three years.

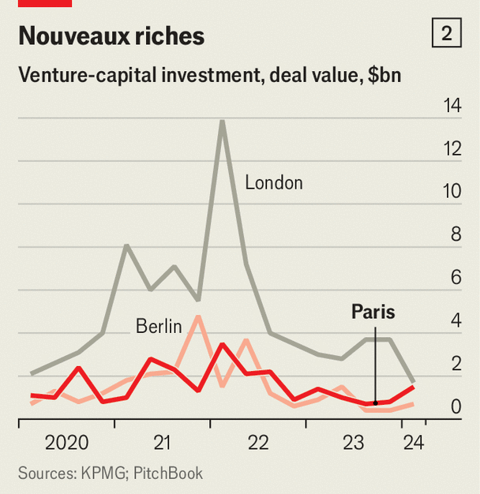

An effervescent startup scene, meanwhile, is drawing in venture capitalists. In the first quarter of this year they invested $1.5bn in Paris-based startups, according to KPMG, an advisory firm (see chart 2). Around $500m of that went to firms working on “generative” artificial intelligence (AI) of the sort that makes ChatGPT a human-like conversationalist. Their counterparts in London, historically Europe’s premier tech hub, attracted just $100m in the same period. Only America and China are home to a greater number of “notable” machine-learning models, according to a report by Stanford University.

Of the 100 billion-dollar startups to watch in Europe, 21 are French, according to GP Bullhound, an advisory firm, neck and neck with Britain (which has 22) and far ahead of Germany (with 14). A recent report by Accel, a venture-capital (VC) firm, notes that former employees of 28 such “unicorns” in France have gone on to establish 186 new startups between them. And, as one VC investor puts it, in tech, “France is Paris—and Paris is super-hot at the moment.”

In contrast to the previous wave of French startups, which offered domestic e-commerce and mobile services, the latest lot harbour grander ambitions from the get-go, notes Philippe Botteri of Accel. Founders of new AI firms “now immediately have a global pitch”, agrees Xavier Niel, a telecoms mogul turned venture capitalist and founder of Station F, a bustling tech incubator in Paris.

Catching a second wind

Mistral AI, a maker of cutting-edge generative-AI models, is now talked about with the same breathlessness as OpenAI, creator of ChatGPT. This month it raised €600m in a funding round that reportedly valued it at nearly €6bn. In May H, a fellow Parisian AI darling formerly known as Holistic AI, announced a $220m seed round only months after it was co-founded by a French researcher at Stanford University and four former employees of DeepMind, the AI lab of Google.

What has driven the great Parisian revival? Luck has played a part. After Britain formally left the EU in 2020 bankers were no longer legally able to provide some services to their European clients from London. For those financiers who did not want to decamp from the British capital, Paris, a two-hour train ride away, was easier to get to than Frankfurt. For those who did decide to move, it was a more pleasant place to live. One finance boss recalls asking his London-based traders to move to Frankfurt, only for them to go home, speak to their partners and return the next day saying “absolutely not”. When he posed the same question about Paris, the family reaction was “of course”. (Preferential tax treatment of foreigners for the first few years of their residency did not hurt, either.)

The boom in AI, meanwhile, has put a huge premium on the sort of mathematical skills that have long been the forte of Paris’s renowned technical universities. Two of Mistral’s six co-founders are products of École Polytechnique; a third graduated from École Normale Supérieure. This talent pool drew America’s tech giants such as Google and Meta, which opened big AI labs in Paris. It also helps that France’s nuclear-powered electricity grid can provide lots of clean energy to feed power-hungry AI data centres.

But there is more to the city’s recent streak than just good fortune. Take finance, where France was not merely a passive beneficiary of Brexit. Frankfurt’s banking cluster and proximity to the European Central Bank initially made it the more obvious destination for relocation.

Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, remembers that when the bank was first looking for alternatives to London after Brexit, Paris barely featured in the conversation. Amsterdam, Dublin and Frankfurt were all viewed more favourably. What made a difference, Mr Dimon says, was the French president. Mr Macron made it clear to him that France was open for business, and even went out of his way to suggest a possible location for a trading floor. “This is the first time that we have a president who is a former investment banker, who is fluent in English, who is globally minded, who is pro-business, and who has no inhibition about interacting with the business community,” says Stéphane Boujnah, the French boss of Euronext, a pan-European bourse.

Mr Macron has successfully translated this pro-business attitude into sound and predictable policy. Bruno Le Maire, finance minister since 2017, has held that office for the longest stretch since the modern French republic was founded in 1958 and, in the words of the CEO of a giant global asset manager, “brought a lot of credibility”. He and Mr Macron promised from the start not to raise taxes, and stuck to their word. They introduced a flat tax on investment income and ditched an unloved (and unworkable) wealth tax. The sense of stability and openness has been strengthened further by the regional government under Valérie Pécresse, who has overseen an expansion of the city’s underground network.

Mr Macron’s government was also early to see AI’s potential and the role Paris could play in the technology’s development. It produced its first national AI strategy already in 2018, drawn up by Cédric Villani, a mathematician. Cédric O, one of Mistral’s co-founders, who was previously Mr Macron’s digital minister, says that the critical decision was to woo American big tech. “At the time people said: you are crazy putting out the red carpet for the Americans; they are going to steal your talent.” In fact, the opposite happened. Many Parisian AI founders, including the Mistral trio, left big tech’s research outposts to strike out on their own.

À bout de souffle?

This business-friendly approach may not survive the parliamentary election. Although Mr Macron himself will remain in office until 2027, some of his reforms could be undone. Both Marine Le Pen’s hard-right National Rally and the New Popular Front (NFP), a left-wing alliance led by a former Trotskyist, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, promise to bring back the wealth tax. The NFP would also raise the minimum wage, which could deter job creation. Patrick Martin, head of the MEDEF, a business lobby, has called both their programmes “a danger to the economy”.

In the event of a hung parliament, the most probable outcome, the most extreme of these policies may not be implemented. Even so, politics looks likely to get in the way of Paris’s revival as a global commercial centre. The city benefited from having politicians in charge who understood and welcomed business, and who worked together to draw in foreign talent and capital. With that project almost certain to lose steam after the parliamentary elections, global bosses may find themselves with fewer reasons to drop by. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.