Responding to pressure from conservative groups threatening “anti-woke” boycotts, Jack Daniel’s parent company, Brown-Forman, recently announced that it would end workforce and supplier diversity goals and no longer participate in the Human Rights Campaign’s Corporate Equality Index, citing shifts in the “legal and external landscape.”

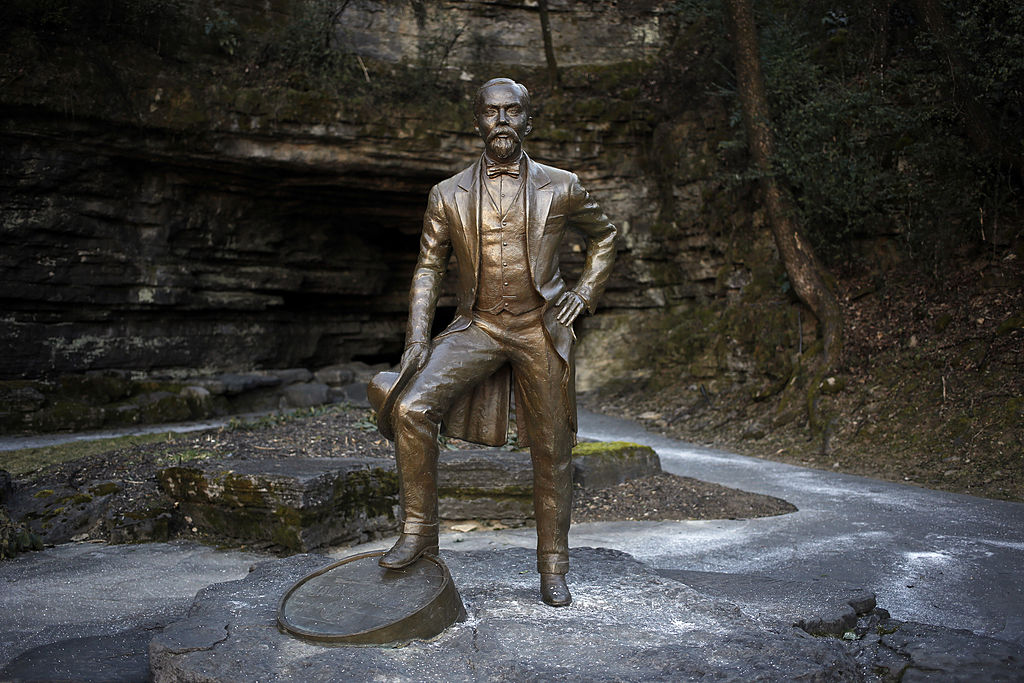

My connection to Jack Daniel goes back to a very different era—one defined by the man himself, Jack Daniel, and the inclusive environment he created at his distillery in the 19th century. The legacy I want to highlight is about his commitment to inclusion and equity, which Jack Daniel, the man, fostered in an improbable time and place: the post-Civil War South, just minutes from the Alabama border. His values of inclusion became a cornerstone of the distillery’s early success and were carried forward by his descendants well into the 20th century.

Jack Daniel’s approach to inclusion was groundbreaking for its time. In the heart of the rural South, where racial division was the norm, Jack Daniel built a distillery where half of his workforce was African American, even though African Americans made up less than 20% of the population in Lynchburg, Tenn. The jobs at Jack Daniel Distillery were some of the most coveted in the area, and it was known that Jack hired based on merit, not race, drawing African Americans from surrounding towns. His fair treatment of workers created an environment where diversity wasn’t just accepted but sought after. Jack Daniel may not have been able to address the systemic or structural issues of the time, but he led with his heart, creating a culture of inclusion that was not only morally right but good for business.

Read more: What the Civil Rights Movement Can Teach Us About Corporate Culture Wars

What made Jack Daniel’s commitment to equality even more remarkable was his humanity beyond the distillery. Upon his death, thousands of unpaid loan notes were found in his possession—debts owed by people of all backgrounds, races, and walks of life. His will was clear: not a single debt was to be collected. Jack Daniel understood that everyone needs a helping hand at some point, and his generosity showed his belief in giving without expecting anything in return.

The fact that Jack Daniel Distillery was able to recover and thrive after Prohibition when so many other Tennessee distilleries closed their doors permanently can be attributed, in part, to the diversity Jack Daniel built into the fabric of his company. By pulling from a wide pool of talent and perspectives, Jack Daniel Distillery had the agility and strength to rebuild when others could not. It is this legacy of inclusion—initiated by Jack Daniel, the man, and continued by his family—that I have built upon at Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey.

At the heart of that legacy is Nearest Green, the African American distilling genius who became Jack Daniel’s first master distiller. Nearest Green taught Jack Daniel the craft of distilling, and the two men formed a bond that was much more than business: Nearest Green was a mentor and a father figure to Jack. After Nearest Green retired, his son, George Green, continued working with Jack as his right-hand man, further embedding the Green family’s legacy into the foundation of the distillery.

Read more: Why Master Distiller Nearest Green’s Story Must Be Told

Jack Daniel, the man, offers a model for the type of DEI we need today. Jack Daniel didn’t need mandates or quotas to treat people equitably. His workforce at the distillery was diverse long before it was required by law. The fact that Jack Daniel was able to foster inclusion in the heart of the South, during an era when such practices were virtually unheard of, is a testament to the strength of his character and the values he lived by. This is the spirit of inclusion that guided Jack Daniel in his day, and it’s the spirit that guides Uncle Nearest now.

As we discuss DEI today, it feels like we’re losing the plot. It shouldn’t be an either/or debate—it’s a matter of “and.” Women and people of color make up 70% of the population, and we are essential to the workforce. But we don’t want special treatment; we want equality—equal pay and equal opportunities.

To understand the backlash against DEI programs, we must acknowledge that the American Dream has eluded many. Often those who don’t fit the typical narrative of disenfranchisement. As we talk about DEI, it’s time to expand the conversation to include socioeconomic status and geography. True diversity and equity must embrace a broader vision of inclusion—one that acknowledges those who struggle regardless of race. It is worth noting that around one in five African Americans live in poverty in the U.S., equaling about 8.5 million people—a disproportionate share of the American population. It is also vital to recognize the 15 million white Americans living in poverty.

I don’t believe most opponents of DEI programs are against diversity, equity, or inclusion. Their issue is with how DEI is currently being positioned. So the question becomes: how do we address historic injustices without creating new ones? Consider this: women in the United States still earn, on average, just 82 cents for every dollar earned by men, while Black women earn only 64 cents. Similarly, Black workers earn just 76 cents for every dollar earned by white workers, regardless of education or occupation. These disparities are not just statistics; they represent real people, people who continue to be left behind in a country that prides itself on equality of opportunity. To those who question DEI in its current form, I implore and challenge you: will you help us move toward equality? Help us find a better path forward.

Jack Daniel gave us the answer long ago: treat everyone with equality, uplift those who are struggling, and help those who need it most. If people want to scrap the term DEI, fine. But let’s not lose sight of the goal: equality. Maybe some current programs aren’t the answer, but what is? If we can’t answer that, dismantling what we have only takes us back to a time when inequality was the rule of the land.