Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

Not since the 1980s have Japanese businesses generated so much excitement. Japanese companies’ profit margins have doubled in the past decade or so. They are forking out twice as much to their owners in the form of dividends and share buy-backs as they did ten years ago. Shareholder-friendly changes to corporate governance in Japan have caused foreign investors to flock to the country once again. Having languished for decades, the Nikkei 225 index, which tracks the value of the country’s largest listed firms, is up by 25% over the past year (see chart 1). In February it at last exceeded the record it set in 1989, just before Japan’s bubble burst.

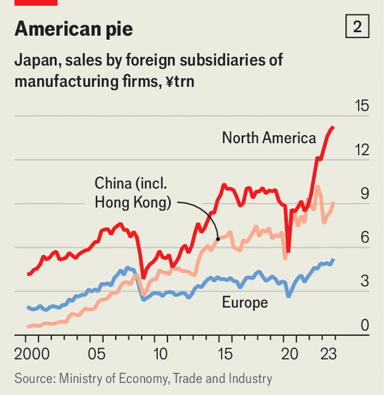

Much of this success reflects Japan Inc’s transformation over the past 35 years. Faced with economic torpor at home, brought on by the stockmarket crash and an ageing population, the country’s industrial giants have spent the past few decades hunting for growth abroad. In 1996 revenue booked by the foreign subsidiaries of Japanese manufacturers was just 7% of their total sales. Last year that figure reached 29%, a record high.

Two markets have been central to this wave of global expansion: America and China. America has long been the largest destination for Japan’s manufacturers. In recent years China has made up a growing share of business. All told, more than half of all sales made by Japanese firms’ foreign subsidiaries comes from one or the other of the two superpowers. Japanese executives therefore understandably view the intensifying Sino-American rivalry with trepidation. Being forced to choose between the two superpowers may, they fear, imperil corporate Japan’s revival.

Some companies appear ready to side with America. A few are shifting manufacturing out of China, often to South-East Asia, in an effort to diversify their supply chains and placate customers worried about geopolitical risks. In September Mitsubishi Motors announced that it would stop making cars in China. It has been expanding production in Thailand and Indonesia instead.

Many are doing the same in America itself. Toyota, a Japanese carmaker, and Panasonic, an electronics firm, are among the companies that already receive more than $1bn apiece in handouts courtesy of state and federal efforts to revive American manufacturing since 2021, according to Good Jobs First, a subsidy watchdog. Rahm Emanuel, America’s ambassador in Tokyo, has been busily courting Japanese investment. American governors regularly visit Japan, in the hope of attracting money and creating jobs in their states. In return for an $8bn investment by Toyota in battery production in North Carolina, the state has provided hundreds of millions of dollars in tax and infrastructure incentives. America’s comparatively strong economic growth is adding to its attraction as an investment destination for Japanese firms. Sales of their subsidiaries in America have surged in the past two years, helped by the strong dollar (see chart 2).

Yet Japanese bosses also grumble about the domestic-content requirements and restrictions on their investments in China that come with some American subsidies. And they fear America’s increasingly volatile politics. The phrase moshi tora, Japanese for “if Trump”, frequently crops up in boardrooms. Many worry that, if re-elected in November, America’s former president could dismantle the current subsidy regime, or alter it to give preference to American firms. Meanwhile, President Joe Biden’s opposition to the acquisition of US Steel by Nippon Steel, a Japanese rival, has shown that protectionism is ascendant on both sides of the political aisle. America is becoming “selfish”, grumbles a Japanese semiconductor executive.

Mistrust of America is one reason why few Japanese firms are prepared to cut ties with China in the way that Mitsubishi Motors has. Even those that reduce their Chinese manufacturing often remain reliant on suppliers across the Sea of Japan. And for many, the Chinese market remains too lucrative to forsake. In April Toyota and Nissan respectively teamed up with Tencent and Baidu, two Chinese digital giants, in an effort to boost the popularity of their cars among technology-mad Chinese motorists. In the past two years annual trade between Japan and China was roughly a third higher than in the late 2010s (see chart 3). “Japan cannot afford to live without China,” says a board member of one large Japanese company.

A big problem for Japanese companies intent on staying in China is that China seems increasingly able to live without Japan. In many industries Chinese competitors are giving Japanese rivals a run for their money. A chemicals-industry executive in Tokyo complains that Chinese rivals have gained an advantage by procuring cheap energy and materials from Russia, which is out of bounds for Japanese companies owing to Ukraine-related sanctions. But low cost is not Chinese industry’s only selling point. Many are offering increasingly sophisticated products, especially in areas once dominated by Japan, such as industrial automation, batteries, carmaking and electronics.

Chinese cars, especially electric ones, have been edging out Japanese vehicles both in China and in other Asian markets. CATL, a Chinese battery behemoth, has out-innovated Japanese rivals such as Panasonic. In February Junta Tsujinaga, chief executive of Omron, a Japanese maker of industrial robots, lamented that his firm was facing greater competition from Chinese challengers. It is cutting 2,000 jobs from its global workforce this year.

Japan’s cutting-edge semiconductor firms may be next. As America tightens restrictions on sales of advanced technologies to its geopolitical rival, the Chinese government is trying to reduce its reliance on foreign providers of such things as chips, as well as the materials and tools used to make them. According to Bernstein, a broker, the domestic market share of Chinese makers of equipment used in chip manufacturing rose from 4% in 2019 to an estimated 14% last year. This is a concern for Japanese chip-industry champions such as Tokyo Electron, a manufacturer of equipment to process silicon wafers and Japan’s fourth-most-valuable company, which generates almost half its total sales in China. Such worries will be compounded if, as seems all too likely, American sanctions are extended to the older technologies which Japanese firms are still selling to Chinese buyers.

To navigate the minefield of great-power rivalry, a growing number of Japanese firms are war-gaming how politics could disrupt their businesses. “Economic security” is the latest buzzword. A survey of large Japanese companies by the Institute of Geoeconomics, a think-tank in Tokyo, found that 38% had established economic-security departments. The divisions, which often report directly to a board member, monitor political risks to the company’s operations and supply chains. Many large companies that are particularly exposed to geopolitical winds receive money from Japan’s government to support such efforts.

Knowing where they stand can be a source of solace for Japanese firms. Another is improving relations across East Asia’s wealthy democracies. Governments and businesses in South Korea and Taiwan face similar challenges in maintaining crucial economic relationships with both America and China.

In an interview with Nikkei, a Japanese newspaper, on May 23rd Chey Tae-won, chairman of SK Group, a South Korean conglomerate with a leading memory-chip business, said that his company would expand tie-ups with Japanese semiconductor firms. TSMC, a Taiwanese giant that is the world’s leading manufacturer of advanced microprocessors, opened its first factory in Japan in February, and has announced plans to build a second.

Domestic bliss

An increasingly unpredictable outside world is also leading some Japanese companies to retreat to the comfort of home. It helps that, while manufacturing wages have surged in China, Japan’s sluggish growth has made repatriating production relatively less expensive than it once was. The government has also granted modest subsidies to hundreds of companies in industries deemed sensitive, including aircraft parts, medical devices and rare-earth minerals (which are used in electronics). Last year Panasonic announced it would shift some production of air-conditioners from China to Japan. Such moves may calm Japan Inc’s nerves. But if this foreshadows a less globalised future, they may also stall its comeback. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.