Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

“TEXAS IS AN El Dorado for us, an energy El Dorado,” declared Patrick Pouyanné, boss of TotalEnergies, last month at CERAWeek, the energy industry’s annual shindig in Houston. He unveiled an expansion of the French supermajor’s shale holdings in the south of the state, a deal intended to bolster its position as the leading exporter of American liquefied natural gas. It had earlier bought three Texan gas-fired power plants and opened a new electricity-trading desk in Houston. Meanwhile in Brazoria, a windswept county an hour’s drive from the city, it has built a solar park capable of producing 380 megawatts (MW) of clean power, and of stashing some of the resulting joules in a bank of lithium-ion batteries made by Saft, its energy-storage arm. Hundreds of sheep and the odd gazelle graze among 700,000 photovoltaic panels on its 2,300 acres (930 hectares), with not a nodding donkey in sight. “You love energy here in all forms, from gas to renewables,” Mr Pouyanné told the oilmen at the Houston gabfest.

This ecumenical strategy is TotalEnergies’ attempt to bridge its industry’s transatlantic divide when it comes to the energy transition. The French firm’s big European rivals, BP and Shell, invested heavily in “electrons” businesses like wind and solar energy—until weak returns and sagging share prices forced them into embarrassing U-turns. Its American counterparts, ExxonMobil and Chevron, have instead doubled down on oil and gas, while backing “clean-molecule” businesses like hydrogen and carbon capture—and have been rewarded with higher valuations.

Mr Pouyanné thinks he can straddle both worlds. His firm will continue to invest in “System A”, as he calls the oil and gas that the world still needs. Examples include its recent hydrocarbon projects in Brazil, Suriname, Namibia and the United Arab Emirates. Here Mr Pouyanné’s imperatives are reducing the amount of carbon released in extracting the crude and, critically, slashing production costs, down to “less than $20 a barrel”, he says. If barrels keep trading for around $90, this should spin out plenty of cash to invest in “System B”, the low-carbon business that needs to grow fast if global climate goals are to be met. TotalEnergies has or is building some 5,000MW of clean-power capacity in Texas alone, making it one of America’s biggest backers of such ventures. It plans to devote 30% of its capital spending, or around $5bn a year globally, to low-carbon electricity, twice as much as a typical major. By 2030 it wants to produce over 100 terawatt-hours annually, enough to light up Arizona. Perhaps a quarter of those terawatt-hours would be generated in America.

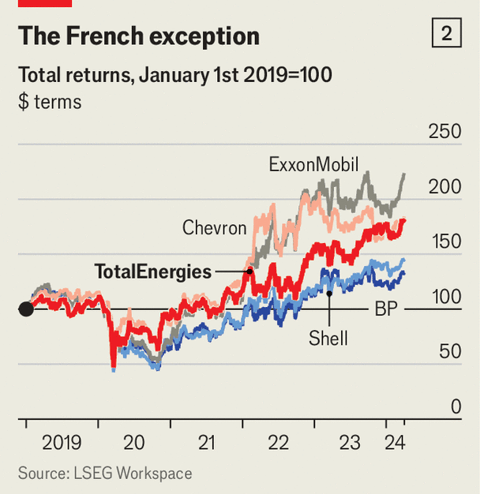

What makes TotalEnergies’ green plans distinctive is that it has found a way to make good money from them. Last year its return on capital was nearly 20%, higher than all its big rivals (see chart 1). As a result, since 2019 its shareholders have enjoyed a total stockmarket return, including dividends, of nearly 80%, roughly in line with Chevron’s and around twice those of BP and Shell (see chart 2).

One big reason renewable energy suffers in the marketplace is intermittency. In time lots more grid-scale batteries like those installed in Brazoria will cleanly complement its wind and solar. Until then TotalEnergies will use gas turbines as “flexible” backup to manage windless days and sunless nights. A big chunk of the profits from its low-carbon-electricity business last year came courtesy of those gassy “flexible-generation” assets.

The dual strategy is a byproduct of TotalEnergies’ history. CFP, in its original French acronym, was founded 100 years ago to ensure France’s energy independence. Initially that involved drilling for hydrocarbons in Iraq. This profitable business ended when the Iraqi oil industry was nationalised in 1972. In 2021 the company returned to Iraq in a spectacular way by securing the lead role in a $27bn energy project. Mr Pouyanné thinks it edged out competitors because it offered financial and technical assistance to help Iraq generate electricity using gas that would otherwise be flared, as well as building 1,000MW of solar power. A similar approach has found favour in Libya, Mozambique and other countries with plentiful hydrocarbons and pitiful power sectors. Now, amid the energy transition, it is gaining ground even in places like America.

Some climate campaigners question this strategy. They see gas, which burns more cleanly than oil or coal, not as a bridge to a greener future but a fossil cul-de-sac. TotalEnergies’ capital-spending plans suggest that view is too cynical. Of its $5bn in annual investments in low-carbon energy, 93% is going to renewables and just 7% to gas. By 2028 flexible generation’s share of profits is expected to fall to a quarter, as a surging System B begins to match, and then surpass, a shrinking System A. By 2050 only 25% of TotalEnergies’ sales will derive from oil and gas, according to the company’s climate plan, down from 90% today. The firm envisages that electricity generation and renewables will make up half its revenues, with hydrogen and renewable biofuels making up the rest. Between now and then it will try to prove that profits and the planet need not be at odds—even for an oil major. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.