IF A POLE runs out of milk on a Sunday morning, they will probably head to Zabka, a convenience store. It is rarely a long walk. Roughly 17m people, nearly half of Poland’s population, live within 500 metres of one of its more than 10,500 outlets. Some may now buy a slice of the retailer itself: on October 17th its owner, CVC, a European private-equity firm, listed a third of Zabka’s shares on the Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE) at a valuation of 21.5bn zlotys ($5.5bn). The deal has brought a boost to Poland’s beleaguered bourse.

Zabka, whose name means “little frog” in Polish, has grown rapidly in recent years. Between 2021 and 2023 its revenue rose from $3.2bn to $5bn. It plans to open 4,500 more shops by 2028, moving beyond cities and into smaller Polish towns, as well as abroad—in May it entered Romania under the name Froo.

Already Europe’s largest convenience-store chain by number of outlets, Zabka has earned its popularity. Its small shops are cleverly designed: customers are in and out in 106 seconds on average. Each store’s inventory is optimised for the appetites of local customers. A snazzy mobile app holds vouchers and receipts and gives customers access to its cashierless “Nano” stores, which are open 24/7. It helps that Zabka is now one of the few places you can get groceries on a Sunday in Poland: it is exempt from trading restrictions introduced in 2019 owing to its franchise model.

Zabka’s choice to debut on the WSE was a rare coup for the struggling stockmarket. Valuations of Poland’s listed firms have not kept pace with the country’s economic growth of late. Its stockmarket took a hit in 2013 when the first government of Donald Tusk, who returned as prime minister last year, overhauled the country’s pensions system. Private pension funds were absorbed into a government system in an effort to reduce the state’s debts, leading to a reduction in investment in the WSE.

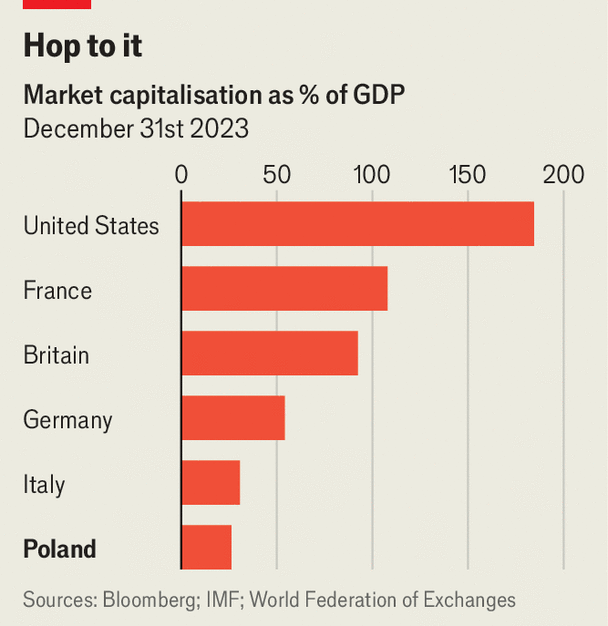

Warsaw’s exchange has been in a doom loop ever since. The market capitalisation of companies listed on the WSE fell from 40% of Poland’s GDP in 2013 to 26% in 2023, putting it well behind other European countries (see chart). Domestic investors have been put off by poor past performance. That, in turn, has sidelined Poland’s stockmarket as a source of funding; in 2021 InPost, a Polish parcel-locker company, chose Amsterdam instead to raise €2.8bn ($3.4bn) in equity. The number of companies listed on the WSE reached a peak of 482 in 2017, but has since steadily fallen to 410.

The WSE is now dominated by state-controlled banks and energy firms. These have often pursued the government’s aims by pouring profits into state-backed projects, rather than dividends, and hiring and firing executives on political whims, says Andrzej Stec, editor-in-chief of Bankier.pl, a Polish financial-news outlet.

Yet there are still good reasons for Zabka to debut in Poland. As the fourth-largest IPO ever on the WSE, it has gained plenty of attention in the country; orders for its shares, priced at the top of their proposed range, were heavily oversubscribed. Jon Eastick, the chief financial officer of Allegro, an online marketplace that listed on the WSE in 2020 in the exchange’s biggest-ever IPO, explains that his firm chose the local bourse to attract retail investors who use its service. Listing in Poland might also be a way for companies to stay in the government’s good books. Changes to the Sunday trading laws are listed first among the risks to Zabka in its prospectus.

More headline-grabbing IPOs like Zabka’s could inject much-needed sparkle into Warsaw’s dull stockmarket, drawing in first-time investors and perhaps charting the way for smaller companies seeking funds. Zabka’s pond may soon grow. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.