Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

CHINA’S HUNGER for homemade chips is insatiable. In May it was revealed that the government had launched the third iteration of its “Big Fund”, an investment vehicle designed to shore up the domestic semiconductor industry. The $48bn cash infusion is aimed at expanding the manufacture of microprocessors. Its generosity roughly matches similar packages from America ($53bn) and the EU ($49bn), both of which are also trying to encourage the expansion of local chipmaking.

Chinese chipmakers are in a tough spot. In October 2022 America’s government restricted the export to China of advanced chips and chipmaking gear made using American intellectual property—which is to say virtually all such devices. This makes it near-impossible for Chinese firms to produce leading-edge microprocessors, the kind whose transistors measure a few nanometres (billionths of a metre) across and which power the latest artificial-intelligence models. But it does not stop them cranking out less advanced chips, with transistor sizes measured in tens of nanometres, of the sort that are needed in everything from televisions and thermostats to refrigerators and cars.

Chips off the old block

As a consequence, semiconductor companies from China increasingly dominate chipmaking’s lagging edge. They account for more than half of all planned expansion in global manufacturing capacity for mature chips. TrendForce, a research firm, forecasts that China’s share of total capacity will increase from 31% in 2023 to 39% in 2027 (see chart 1).

This has alarmed Western policymakers. In April Gina Raimondo, America’s commerce secretary, warned that China’s “massive subsidisation” of their manufacture could lead to a “huge market distortion”. America and the EU have launched reviews to gauge the effect of China’s legacy-chip build-up on critical infrastructure and supply-chain security. Bosses of Western chip firms privately grumble that the coming glut of Chinese semiconductors will put downward pressure on prices both in China, from which foreign chipmakers derive large portions of their revenues, and elsewhere. Even some of their Chinese counterparts agree. They include SMIC, China’s biggest foundry (as contract manufacturers that make chips based on their customers’ blueprint are known). Last month it warned investors that competition in the industry “has been increasingly fierce” and that it expected prices to fall.

Chinese investments certainly suggest ambitious plans. In 2022 China imported chipmaking equipment worth $22bn. The following year it bought $32bn-worth of similar tools, accounting for a third of worldwide sales. Customs data show that in the first four months of 2024 Chinese imports of chipmaking tools were nearly double those in the same period last year (see chart 2). Since American export controls bar the most sophisticated equipment from reaching China, the bulk of those imports are likely to consist of kit used to make lagging-edge chips, not leading-edge ones. Chinese chipmakers have also been buying more equipment from Chinese toolmakers, whose market share at home has risen from 4% in 2019 to an estimated 14%. Because homemade equipment is years behind the technological cutting edge, it is likewise destined for the production of mature chips.

Still, fears that this threatens the security of the West’s supply chains may be misplaced. Jan-Peter Kleinhans of SNV, a German think-tank, reckons most of the new production will be “in China, for China”. In 2018 SMIC and Hua Hong Semiconductor, another foundry, generated nearly 40% of their revenue from foreign customers. This fell to 20% last year. At the same time Chinese foundries’ overall output increased, reflecting robust domestic demand.

This demand looks likely to remain strong. Bernstein, a broker, estimates that Chinese carmakers, electronics firms and other chip users buy almost a quarter of the world’s mature semiconductors. Almost half of those purchases still come from abroad whereas they could be coming from home.

There is another reason for the West to keep its cool. Although Chinese chipmakers rival foreign makers of mature semiconductors in manufacturing, they are still outmatched when it comes to design, engineering and product reliability. This is especially true for fiddly semiconductors such as microcontrollers (a type of computer-on-a-chip) and analogue processors (which use wave-like signals instead of digital ones and zeros). Having doubled their domestic market share to around 12% between 2019 and 2021, Chinese makers of analogue chips have been unable to make further inroads since. Bernstein expects them to supply just 14% of the domestic market by 2026. That leaves lots of room for Western producers such as Analog Devices, Texas Instruments and NXP.

More surprisingly, Chinese foundries are also at a cost disadvantage. In contrast to leading-edge chip factories, which must upgrade their expensive equipment frequently as transistors shrink, most mature-chip manufacturers operate the same equipment for a long time. So long, in fact, that established companies have fully depreciated the value of many of their assets. This significantly lowers their unit costs, a boon at a time when competition keeps prices down. Chinese chipmakers which are investing in new capacity right now will have to absorb the hefty cost of those investments for several years. That means considerably thinner margins and therefore less money to reinvest in future growth. If China’s government wants that growth to continue, the third Big Fund will not be the last. ■

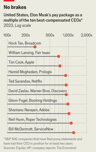

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.