Few parts of the global economy hold more obvious promise than South-East Asia. Multinational firms hoping to move manufacturing away from China are racing to establish supply chains in the region. Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam are expected to be among the fastest-growing economies in the world during the rest of the decade. Malaysia is likely to join the ranks of the world’s high-income economies soon. Singapore’s importance as a financial hub has grown as foreigners have deserted Hong Kong.

But when it comes to home-grown businesses, the picture in South-East Asia is murkier. The market value of investible stocks in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand is around $900bn. Those five economies have roughly the same GDP as India but less than half its investible market value (see chart 1). Seven American companies are each worth more than the entire South-East Asian market.

Among the top 50 firms in South-East Asia by revenue, only one—Sea, a Singaporean gaming and e-commerce firm—was founded in this century. State-owned enterprises account for 15 of the top 50. Subsidiaries of the region’s tentacular conglomerates account for 14.

Sprawling corporate empires with long histories—such as Thailand’s CP Group, Malaysia’s Sime Darby, Indonesia’s PT Djarum and the Philippines’ San Miguel—play an outsize role in South-East Asia. Their portfolios span industries from agriculture, energy and property to banking, telecoms and retail. And they often have deep political ties, which help them thrive in industries that rely on the government for licences and permits. Across South-East Asia conglomerates dominate business—and keep the region from reaching its potential.

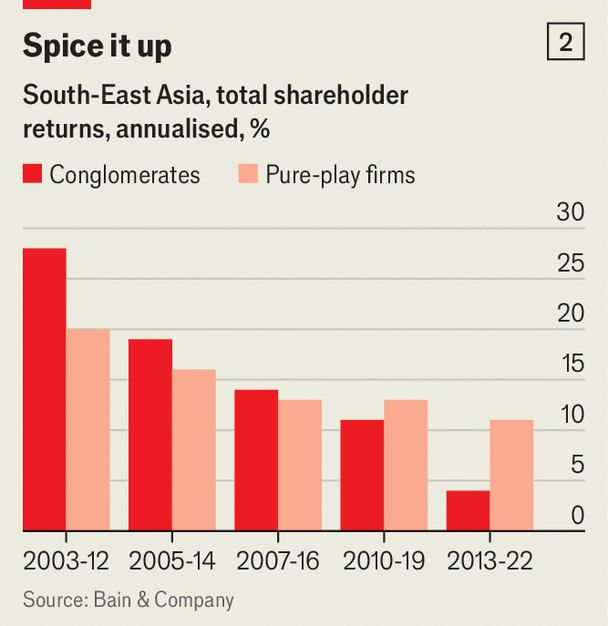

Not long ago South-East Asia’s conglomerates were star performers. Between 2003 and 2012 they generated an annualised shareholder return, including dividends, of 28%, compared with 20% for South-East Asian firms focused on specific markets, according to Bain, a consultancy. That pattern, however, has since inverted: between 2013 and 2022 South-East Asia’s conglomerates generated a meagre 4% annualised return, well below the 11% notched up by the region’s more focused companies (see chart 2).

Partly that reflects a downturn during the latter period in the prices of various commodities the conglomerates sell. But it also reflects the failure of the groups to adapt. “The industries on which these conglomerates grew are mature or declining,” observes Till Vestring, a partner at Bain in Singapore. “Many haven’t managed to move into newer sectors.”

Some conglomerates want to change that. Vingroup, the biggest conglomerate in Vietnam, has launched VinFast, an electric-vehicle brand, and briefly made its own smartphone.

A number of the region’s conglomerates have sought help from foreign firms to move into areas such as e-commerce, digital banking and renewable energy. Sinar Mas, an Indonesian conglomerate, has joined up with LG CNS, the cloud-computing arm of the South Korean giant, to build data centres. Ayala Group, a conglomerate in the Philippines, teamed up with Ant Financial, a Chinese fintech firm, to launch Mynt, an e-wallet provider. Earlier this month Ayala sold half its stake in the venture to Mitsubishi, a Japanese conglomerate, for $319m.

For many of South-East Asia’s conglomerates, though, extensive political ties have dampened the incentive to innovate. Foreign-ownership restrictions shield them from competition, especially in areas like telecoms, banking, media and property. Cosy relationships with regulators keep domestic upstarts at bay, too.

South-East Asia’s conglomerates are also among the biggest sources of funding for the region’s new businesses, and not only through their banking subsidiaries. Many have substantial venture-capital arms. In the Philippines conglomerates like JG Summit and Ayala are big providers of startup funding. Sinar Mas and Lippo Group, another Indonesian conglomerate, are big venture investors in the country. That might be a plus for entrepreneurs who are happy for their businesses to be subsumed into one of the region’s conglomerates. But it is awkward for those who might wish to compete with them.

Influential conglomerates are common across Asia, and may even be beneficial for economies where markets are underdeveloped, by improving the allocation of capital and talent. But the conglomerates of South-East Asia are particularly worrisome. South Korea’s chaebols—family-owned conglomerates such as Samsung, Hyundai and LG—are big and innovative in part because they compete with foreign companies in overseas markets. South-East Asia’s conglomerates, by contrast, focus on their domestic fiefs. When they do sell abroad, it tends to be basic commodities such as agricultural goods.

Focusing on the domestic market may be enough to give India’s conglomerates, such as Reliance Industries and the Adani Group, the efficiencies that come with sheer size. Not so in South-East Asia. Indonesia’s economy, the largest in the region, is a third as big as India’s—and it is around three times as large as those of Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. As a consequence, the conglomerates run by South-East Asia’s tycoons are likely to remain smaller and less productive than those in larger economies.

Barbarians on the shores

The deteriorating performance of South-East Asia’s conglomerates has caught the attention of foreign private-equity (PE) firms that have broken up similar groups elsewhere. KKR and Blackstone are among those that have been expanding their presence in the region. South-East Asia’s conglomerates tend to list only some of their stock publicly, which would make hostile bids tricky. More than half the shares of Malaysia’s YTL, the Philippines’ SM Investments and Thailand’s ThaiBev are privately held. But plenty of opportunities exist to nibble around the edges. In August CVC, a European PE firm, purchased a majority stake in Siloam International Hospitals from Lippo Group for more than $1bn.

Still, the shallowness of local capital markets makes a subsequent listing of these businesses tricky, and appetite from foreign investors for modestly sized Asian businesses is limited. Without more competition, South-East Asia’s corporate morass will continue to blight its otherwise optimistic economic story. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.