Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

When the Alternative for Germany (AfD, from its German initials) was launched in 2013, it was a pro-business, classically liberal party created by German intellectuals opposed to the single European currency. Hans-Olaf Henkel, a free-market enthusiast and former boss of the bDI, the main German industry association, was a founding member.

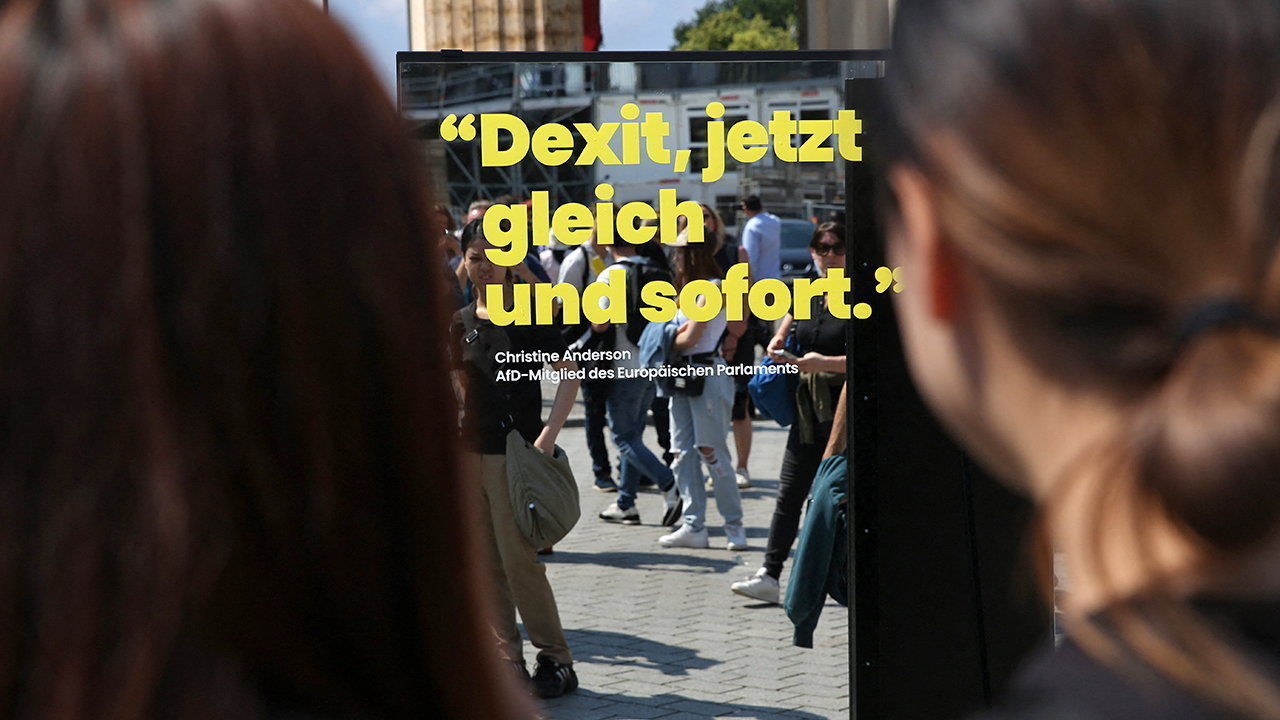

Then, in the space of a few years, the AfD turned into an anti-immigrant, populist party toying with Dexit—Germany’s exit from the eu. Mr Henkel quit in 2015. German bosses turned their backs. Despite being generally reluctant to voice political opinions, many came out strongly against the AfD ahead of the election to the European Parliament on June 9th.

In March Reinhold Würth, the 89-year-old founder of Würth, a hardware firm, wrote to his 25,000 employees in Germany, advising them not to vote for the AfD. The bDI’s current head, Siegfried Russwurm, kept reminding audiences that, as a big exporter, Germany benefits from openness, international trade and European unity. The rise of a party that questions these precepts is extremely dangerous for the German economy, he warned.

Two days before the poll around 30 mainly German firms—including Siemens, a engineering giant, BASF, a chemicals one, carmakers such as BMW and Mercedes, and Deutsche Bank—released a video titled “We Stand for Values”. In it they praised diversity and openness, warned that intolerance damages the economy, highlighted the importance of European integration to prosperity and encouraged their 1.7m employees in Germany to vote. The AfD was not mentioned by name. But the anti-extremist message was clear.

It fell on deaf ears. The AfD won 16% of the nationwide vote, ahead of the Social Democratic Party of Chancellor Olaf Scholz. Only the opposition Christian Democratic Union did better. The AfD is likely to take first place in Saxony, as well as two other eastern states that hold elections in September.

This spooks corporate Germany. A survey of 900 business leaders last month by IW, a think-tank, found that almost 70% saw the AfD’s rise as a risk to Standort Deutschland, shorthand for Germany as a place for business and investment. They fret in particular about what it means for the survival of the EU and the euro. According to a recent IW study, Dexit would reduce Germany’s GDP by 5.6% within five years (as much as both the covid-19 pandemic and the energy crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine combined) and result in around 2.5m job losses.

In its relations with its country’s corporate elites the AfD may be where France’s National Rally (RN), another insurgent right-wing outfit, was a few years ago, says a French diplomat in Berlin. Back then meetings with Marine Le Pen, the rn’s leader, were taboo for CEOs of French blue-chip firms. That cordon sanitaire has become porous as the RN has gained electoral strength. Jordan Bardella, its telegenic president, and Ms Le Pen spent months in the run-up to the EU election courting business leaders. In November Ms Le Pen had a much-noted lunch at a chic Parisian brasserie with Henri Proglio, the former boss of edf, an energy giant. She has also met members of the Dassault clan, a family of aeronautics billionaires.

The RN’s showing in the EU poll, where it came first with 31% of the vote, and the snap French parliamentary election called for June 30th, make the party impossible for French bosses to ignore. Their German counterparts still hope not to have to bend the knee to the AfD. But they are bracing themselves nonetheless. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.