Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

In the electronics department, every television is tuned to the same channel, showing a commercial for a cosmetics brand. At the end of the aisle is a sponsored stall promoting bags of popcorn. The music wafting through the air on the in-store radio is occasionally interrupted by advertising spots. Even at the checkout, a few final commercials pop up on screen to catch customers before they leave.

Anyone strolling around a branch of Walmart, as more than 200m Americans do each month, will see thousands of goodies on offer. Increasingly, its shoppers are being served up as products, too. Walmart, the world’s top retailer by sales, has discovered that there is serious money to be made in selling access to its customers. On May 16th the company reported that its booming advertising business had helped it deliver a 9.6% increase in operating income, year on year, for its quarter ending in April. As it carpets its physical and virtual stores in commercials, the company is taking a growing share of the ad market.

Walmart shifted more than $600bn of stock last year, from televisions to toilet rolls. By comparison its ad operation looks insignificant, bringing in just $3.4bn in revenue in the same period. Yet the margins on advertising are so fat, and those on groceries so thin, that ads contribute an outsized share of profit. In 2023 advertising made up 7.5% of Walmart’s earnings before interest and taxes, estimates UBS, a bank. It reckons that Walmart’s ad business is set to grow by about a quarter every year, contributing 13% of profit by 2026.

Walmart is still an ad-industry tiddler compared with Amazon, its online nemesis, which sold $47bn in ads last year. But the retailer is already comfortably within advertising’s second tier, and is expected to finish the year ahead of social networks such as Pinterest, Snapchat and X. The company has “enormous potential” as an advertiser, reckons Andrew Lipsman of Media, Ads + Commerce, a consultancy.

Walmart’s advertising operation has three main parts. The largest is the digital ads that appear on its website and app. These are closely targeted, because Walmart knows what the consumer is searching for, and their effectiveness precisely measured, since it knows whether shoppers end up buying the advertised product. Because this is “first party” data, from Walmart’s own site, it is unaffected by the ever-stricter anti-tracking rules imposed by Apple and others to protect users’ privacy.

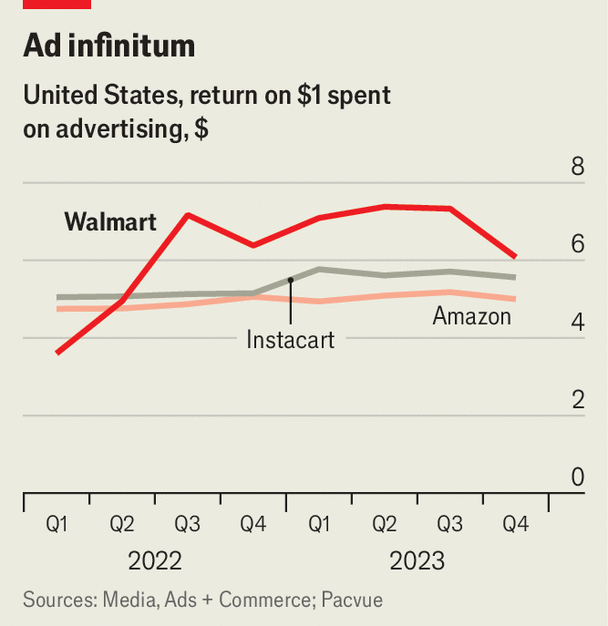

Brands used to grumble that Walmart’s digital ads were poor value. No longer. In 2021 the company poached Seth Dallaire, a star adman, from Instacart, a grocery-delivery firm. Mr Dallaire, who had previously set up Amazon’s advertising business, overhauled the way Walmart’s online ads were auctioned, with the result that these now deliver a better return for advertisers than those of either Amazon or Instacart (see chart). In April third-party “marketplace” sellers were also given the ability to buy display ads on Walmart.com.

The second part of Walmart’s ad offering is video. Again, it is playing catch-up with Amazon, which is pouring billions into shows like “The Lord of the Rings” on its ad-supported streaming service, Prime Video. Walmart has opted for a less glamorous, behind-the-scenes role. In February it said it would buy Vizio, a manufacturer of smart TVs with 18m users in America to whom it can show personalised commercials. And it has done deals with other media companies to target their viewers with its data. The latest of these, announced earlier this month, will see data on Walmart’s shoppers being used to send personalised ads to Disney’s streaming viewers.

Some believe the next step is “shoppable TV”, in which audiences buy products directly through their TV sets. In November Walmart released “Add to Heart”, a TV series stuffed with shoppable products. The “rom-commerce”, as Walmart dubbed the show, will not win any Oscars, but is a revealing experiment. Shoppable TV “is very much in the early innings”, says Sarah Marzano of eMarketer, a firm of analysts, who believes it will take off only if retailers can reduce the friction involved in making a purchase. (“Add to Heart” relied on texting a link to tv viewers’ phones for them to complete the transaction.)

The final advertising opportunity for Walmart, with perhaps the biggest potential, lies in its vast network of bricks-and-mortar shops. Walmart has more than 5,000 stores in America (including its Sam’s Club subsidiary) and 10,000 worldwide, adding up to more than a billion square feet of retailing—and advertising—space. That puts it far ahead of Amazon, which has 538 Whole Foods Market stores and fewer than 100 Amazon Fresh and Amazon Go outlets. Walmart claims that 90% of American households shop at its stores at least once a year. Reaching that in-store audience is the “next frontier”, says Ryan Mayward, an executive at the company.

Advertisers, who are hooked on precisely measurable digital ads, still see in-store ones as poor substitutes. A survey of consumer-packaged-goods firms in 2022 by Bain, a consultancy, found that only 17% believed in-store ads offered a high return on investment. Tracking consumers’ behaviour is harder offline, and some efforts to do so have backfired. Amazon filled its stores with video cameras, but removed some of them after customers grumbled about being spied on. Walgreens, a pharmacy chain, planned to install thousands of ad-filled digital screens on its refrigerator cabinets, but changed course last year, citing various technical problems.

Walmart has improved its ability to link online ads to offline sales, using anonymised payment details to track when a customer buys a product in-store after seeing it advertised in the app. And it is increasing the number of places where advertisers can display in-store messages to consumers. Its stores already show ads on 170,000 digital screens across their electronics departments and checkouts, and are now experimenting with showing them on the screens at their deli counters and bakeries.

In-store digital advertising remains a far smaller market than the online sort, even though 85% of retail sales in America are still made in person. That imbalance may represent an opportunity: if in-store ads can be made remotely as effective as online ones, a market worth tens of billions of dollars awaits, believes Mr Lipsman. Few companies stand to benefit more than the mightiest retailer of all. ■

Correction (May 28th): The original version of this article said Walmart has over a million square feet of retail space. In fact, it has over a billion.

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.