Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

Tim Cook, boss of Apple, is having a rough start to 2024. In the past month his company has faced an unusual barrage of unpleasantness. A patent dispute forced it to remove features from two of its smartwatches. It found out that America’s Department of Justice (DoJ) would be suing it over antitrust transgressions. And it reported that it was losing market share in China, its second-biggest smartphone market. Adding insult to injury, a few Wall Street analysts said something unthinkable until recently—that Apple’s shares were overvalued. On January 11th Microsoft, a rival tech titan, duly dethroned the iPhone-maker, temporarily, as the world’s most valuable company.

The run of bad news may continue on February 1st, when Apple reports its latest quarterly earnings. Equity researchers estimate that its revenues barely grew in the last quarter of 2023, if at all. Then, on February 2nd, Apple will be tested once again. It will start shipping the Vision Pro, an augmented-reality (AR) headset that it has been working on—and talking up—for a few years. The high-end gadget, which will sell for $3,499, represents a big bet on a new technology “platform” that, Apple may be hoping, could one day replace the smartphone as the core of consumers’ digital experience—and the iPhone as the source of its maker’s riches. Early indications hint that Apple should worry about the device’s prospects. Netflix, Spotify and YouTube have announced that they will not make their popular streaming apps work on the headset. None said why. But it could be because they all compete with Apple’s own streaming services, and developing an AR app is likely to be costly.

Mr Cook can brush off some of these worries. Despite everything, Apple’s share price has not moved meaningfully in January. A few days after being overtaken by Microsoft, it reclaimed its heavyweight stockmarket title—and its $3trn valuation. And if the Vision Pro’s launch is a flop, the short-term effect on Apple’s revenues will be nugatory, given the headset’s limited initial production.

Nevertheless, Apple’s boss would be unwise to dismiss the new year’s niggles. For they point to larger challenges for the company. These fall into three broad categories: antitrust and legal issues; slowing iPhone sales; and growing geopolitical tensions. None of these is existential right now. But each carries with it a risk of causing a big upset. Could they cost Apple its position as the world’s most valuable company for longer than a week or so?

Though Apple’s market value has been among the world’s top ten since 2010, until a few years ago it traded at a low valuation relative to profits. It was thought of as a maker of hardware, a business that is more difficult to scale than software. For much of the 2010s its price-to-earnings (p/e) ratio, which captures investors’ expectations of future profits, was below 20, comparable to that of HPE or Lenovo, boring computer-makers with low growth and tight margins. It was also below the average for big American companies in the S&P 500 index (see chart 1).

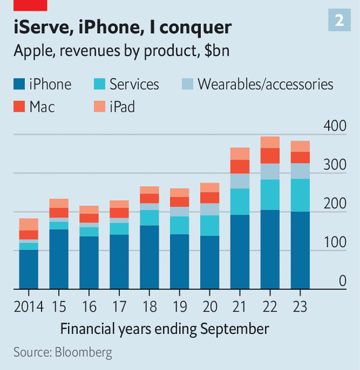

This started to change around 2019, notes Toni Sacconaghi of Bernstein, a broker. Revenue from Apple’s “services” business, which provides software to its devices’ 1bn or so users, began to grow. The two biggest parts of this category are an advertising business, which Bernstein puts at $24bn a year (including around $20bn a year from Google for making the search engine the default option on Apple’s devices), and the App Store (another $24bn). Services also include Apple Music and Apple TV, its streaming offerings, as well as a fast-growing payments business. All told, revenues from services amount to $85bn a year, or a fifth of total sales. In 2016 they contributed just $24bn, or a tenth of overall revenues (see chart 2).

This helped convince investors that Apple was no longer a stodgy hardware provider. It was a software platform, where new paying users could be added at little extra cost. That meant higher profits—the gross-profit margin for Apple’s services arm is 71%, compared with 37% for devices—and more recurring revenue. As services became a bigger part of the business, Apple’s overall profitability swelled, too, from 38% in 2018 to 44% last year. That was also aided by the fact it was selling more high-end, high-margin iPhone models. All of this helped lift Apple’s p/e ratio to around 30, comfortably above the S&P 500 average and higher than that of Alphabet (Google’s parent company), though still below Microsoft’s (38) and Amazon’s (72).

One set of risks that could undo Apple’s p/e progress has to do with its legal headaches. Some, such as the patent problem, look like minor threats. In October the International Trade Commission, a federal agency, ruled that Apple infringed patents related to an oxygen-measuring sensor that were owned by Masimo, a medical-device maker. Apple stopped selling the models which contained the offending technology. But on January 18th it started to sell them again, after disabling the disputed sensor.

Apple’s bigger legal problems have to do with its services business. In March new rules will come into effect in the EU, a huge market, that force Apple to allow apps to be installed on its devices without going through its App Store. That makes it harder for it to charge the 30% fee it levies on most in-app purchases (Apple has filed a lawsuit against the rules).

In America, the DoJ is reportedly looking into whether Apple’s smartwatch works better with the iPhone than with other smartphones and why its messaging service is unavailable on rival devices. If, in a separate case against Google, the courts agree with the DoJ that its default-search deals with device-makers are anticompetitive, Apple could be deprived of roughly $20bn a year in virtually free money. As a result of a lawsuit filed in 2021 by Epic Games, a video-game developer, Apple has already had to change the way the App Store charges developers to sell apps there.

The orb is in your court

Apple is not defenceless in the legal battles. It quickly found a workaround to the Epic-induced changes to its App Store policy that lets it keep collecting hefty fees. A final ruling in the DoJ’s case against Google is probably years away. The same is true of its expected case against Apple. As with many antitrust cases against big tech, investors seem unfazed.

The company is more vulnerable to the second area of concern—its slowing core business. According to a poll of analysts, Apple sold about 220m iPhones last year, barely more than the 217m it shifted in 2017. In 2024 the number might not be much higher. For a while, Apple could offset the slowing volumes with higher prices. But annual revenue growth has slipped to 2% in the past two years, down from an average of 10% between 2012 and 2021.

Some rivals are trying to eat into Apple’s market share in high-end devices by exploiting consumers’ appetite for ChatGPT-like “generative” artificial intelligence (AI). Samsung, a South Korean tech titan, said that it would launch a new range of AI-powered phones by the end of January. Flashy features will include real-time voice translation and turbocharged photo- and video-editing. The devices may be on sale eight months before Apple’s next iPhones. Apple, by contrast, has said little about its plans for the hottest thing in tech since, well, the iPhone. “We’re investing quite a bit,” Mr Cook noted cryptically on the company’s most recent earnings call.

Apple is also being given a run for its money in China, the source of 17% of its overall revenues. According to Jefferies, an investment bank, Apple’s share of smartphones in the country declined last year. Meanwhile that of Huawei, a domestic tech champion, grew by around six percentage points. In August Huawei stunned industry-watchers—and America’s government, which has for years barred sales of American technology to the firm on national-security grounds—by launching the first 5G device containing advanced chips that were Chinese-made rather than imported. Patriotic shoppers in China snapped up the phone and, for good measure, other Huawei devices.

When it comes to AI, worries about Apple’s progress may be overstated. Erik Woodring of Morgan Stanley, an investment bank, points to signs that the company is indeed investing quite a bit. In October the firm’s boffins and researchers at Columbia University jointly released an open-source AI model called Ferret. Two months later Apple published a paper about how such models could run on smartphones, which are much less powerful than the data centres typically used for the purpose. In January a South Korean tech blogger reported that an update to Apple’s operating system possibly as early as June would include AI enhancements for Siri, its robot assistant. Rumours swirl that Apple is planning to use generative AI in its own search engine.

China, however, represents a bigger threat—and not just because of a revitalised Huawei. Apple’s plans for future growth depend in large part on success in emerging markets, including the biggest one of all. Mr Cook kicked off Apple’s past three earnings calls by talking about the company’s sales outside the rich world. China was doubtless on his mind.

Apple is also exposed to China risk through its supply chain. Despite much-publicised efforts to move some production to India, around 90% of iPhones are still manufactured in Chinese factories. So are most Mac computers and iPads. Mr Sacconaghi of Bernstein says that Apple will be hugely exposed to a serious geopolitical escalation, such as a conflict over Taiwan, for at least the next five years.

Events short of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan could also hurt the company. The return of Donald Trump to the White House, a serious possibility now that he has all but wrapped up the Republican nomination, would almost certainly raise barriers to trade and heighten Sino-American tensions. Even if Joe Biden defeats Mr Trump in the presidential election in November, he is hardly a China dove. The Chinese government is beginning to hit back against American sanctions. It has already banned products made by Micron, a chipmaker from Idaho, from some infrastructure projects. In September reports surfaced of a ban on Apple products among government officials. Although the authorities later denied the claims, the episode put investors on edge.

Any Chinese action that hurts Apple in China would hurt China, too. Apple says 3m people work in its supply chain. Many of those workers are Chinese. One analyst likens Apple’s position vis-à-vis China’s government to “mutually assured destruction”. The same could be said of the commercial balance between America and China. Try explaining that to Mr Trump. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.