Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

In the summer of 1994 a job vacancy for software engineers was posted on Usenet, an early precursor to online forums. The company in question planned to “pioneer commerce on the internet”. Eligible applicants needed to be capable of designing complex systems “in about one-third the time that most competent people think possible”. Résumés were to be addressed to Jeff Bezos at a Seattle-based startup named Cadabra.

The name didn’t stick—on phone calls “Cadabra” was too easily confused with “cadaver”—but the ambition did. Amazon, which turns 30 on July 5th, has indeed changed the world of online shopping. This year its websites will sell an estimated $554bn-worth of goods in America, reckons JPMorgan Chase, a bank. That gives it a 42% share of American e-commerce, far beyond the 6% captured by Walmart, its nearest online competitor (and the country’s biggest retailer overall).

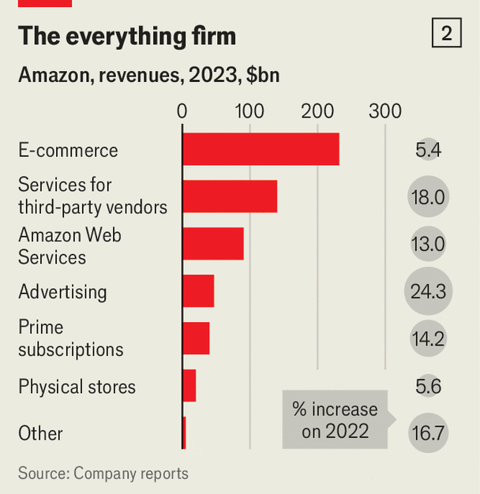

And Amazon did not stop its pioneering at retail. It subsequently invented the Kindle, an e-reader, Alexa, a smartspeaker and, more consequentially, cloud-computing—Amazon Web Services (AWS) has a 31% share of that $300bn market, according to Synergy Research, a data firm. It also runs Prime Video, America’s fourth-most-watched video-streaming service. Its newish, high-margin advertising business is already the third-largest in the world behind Alphabet (Google’s parent company) and Meta (Facebook’s). One subsidiary, Zoox, is building self-driving cars. Another moon-shot project, Kuiper, which is developing a fleet of communications satellites in low-Earth orbit, quite literally aims for the heavens.

On June 26th Amazon got an early birthday present, when the market value of its tech empire surpassed $2trn for the first time (see chart 1). As with all such milestones, however, Amazon’s 30th anniversary is not just a moment to celebrate its achievements but also to look ahead. The big question that hangs over the company as it enters its fourth decade is how to deal with its increasing sprawl (see chart 2).

In the words of a former executive, Amazon’s business units are “rather independent” of each other. Often this was by design. At first AWS was operated at arm’s length from the rest of Amazon, because the firm did not want to give the impression that it was selling spare computing power during Amazon’s off hours, says Rick Villars of IDC, a research firm. Later Mr Bezos wanted to separate the ads business from e-commerce so that the retail arm would not become overly dependent on the advertising unit’s fat margins. More recently some investors have even called for the cloud business to be spun out altogether, in the belief that this would create shareholder value.

Instead, Amazon’s fourth decade looks poised to be an era of integration. The company has grown to the size that any needle-moving new investment is costly and high-risk. Andy Jassy, the former boss of AWS whom Mr Bezos installed as his successor as CEO in 2021, therefore appears keen to generate value by stitching the company’s existing businesses together more tightly. Mr Bezos, who for now retains a 9% stake and a big say over strategy, seems to approve. This metamorphosis would make Amazon more similar to Apple and Microsoft, two older big-tech rivals which have bundled and cross-sold their way to world domination in consumer devices and business software, respectively—and to $3trn valuations.

One patch where Mr Jassy already has his sewing kit out is retail and advertising. The thread running through the two businesses is Prime, Amazon’s subscription service, which has 300m-odd members around the world, providing shoppers with free delivery and access to Prime Video. Prime members spend twice as much on Amazon’s websites as non-members do and they tend to be logged in more often. Amazon also has intimate knowledge of their shopping behaviour, which allows it to target ads more accurately.

Ad value

Advertisers are willing to pay handsomely for this service: analysts estimate that Amazon’s ads business enjoys operating margins of around 40%, higher even than those of the cloud operation, not to mention the much less lucrative retail division. Most of these adverts, responsible for four-fifths of the company’s ad sales, are nestled among search results on its app or next to information about products. But a growing share is coming from third-party websites and, most recently, from Prime Video. In January Amazon started showing commercials to viewers in America, Britain, Canada and Germany.

Only one in seven Prime members is expected to fork out the additional fee ($3 per month in America) for ad-free streaming. That leaves perhaps 260m Prime members who are potential viewers of ads on the platform. JPMorgan Chase reckons that video ads alone will boost Amazon’s ads sales by about 6% this year, adding $3bn to the top line. Given the ad operation’s fat margins, the impact on profit will be considerably larger.

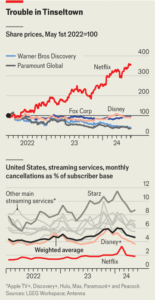

To turn more Prime members into actual ad-watchers, Amazon is splurging on content. It recently signed a contract with MrBeast, a YouTube superstar, rumoured to be worth $100m. It is trying to seal a deal in which it would pay $2bn a year for the rights to show National Basketball Association games on Prime Video. It is already reportedly spending $1bn annually to stream some National Football League (NFL) fixtures.

This hefty price tag is worth it, the company thinks, because popular sporting moments, such as “Thursday Night Football”, have turned out to be among the biggest sign-up days for Prime. And, as Mike Morton of MoffettNathanson, a research firm, points out, adverts aired during sports events are some of the most lucrative in all of the ads business.

Mr Jassy’s bigger task concerns making the retail business and AWS into a more seamless whole. Prime once again has a role, albeit a smaller one: the cloud unit helped Prime Video win NFL streaming rights because the deal terms demanded ultra-reliable internet infrastructure that AWS could provide more easily than rival bidders (fans of live sports would not brook buffering).

Other salient stitches include deals such as a recent one with Hyundai, which included making AWS the South Korean carmaker’s main cloud provider as well as selling its cars on Amazon websites. Analysts speculate that clever AWS software may also be assisting the retail operation’s 750,000 warehouse robots in sorting shoppers’ packages. And having a business as gigantic as Amazon’s retail arm as a captive customer gives AWS the confidence to scale up, helping spread costs.

Stitch-up job

The most important thread stitching Amazon’s two main businesses together is generative AI. Most rivals will struggle to match Amazon’s access to specialised AI hardware, which is in short supply but which it has in abundance thanks to long-standing commercial partnerships with companies like Nvidia, which makes advanced AI semiconductors.

Amazon has already launched a number of products that use the technology, including a tool that sums up customer reviews, a virtual shopping assistant and an image creator for advertisers. Sellers on its e-commerce platform can use the same technology to speed up the creation of product listing pages by, say, pointing the software at their personal website where the good is already sold. Amazon’s nascent pharmacy business is using generative AI to help fill prescriptions and manage stocks of medications. The retail division, for its part, provides a vast trove of data on which to train AI models, which can then be offered to AWS customers.

The company’s ever tighter integration may not be to everyone’s liking. Binding the e-commerce, streaming and cloud businesses closer together may put off AWS’s big clients such as Netflix, which competes with Amazon in streaming, or Ocado, a rival online grocer.

Regulators are even more suspicious. Last year America’s Federal Trade Commission (FTC) brought a lawsuit against Amazon, accusing it of monopolistic practices such as discriminating against sellers that offer products more cheaply elsewhere on the internet and locking merchants into its fulfilment network. The agency has called for penalties “including but not limited to structural relief”—trustbuster-speak for a break-up. Amazon denies the charges.

Investors seem to shrug off such concerns. Amazon’s recent share-price rise was uninterrupted by the FTC lawsuit. And for every cloud customer that AWS loses to rivals such as Microsoft Azure or Google Cloud Platform, it could win one that is repelled by Microsoft’s and Google’s new businesses in their own increasingly tightly knit empires.

Indeed, the greatest risk to Amazon thriving as a 30-something is not antitrust cops or cross cloud-computing clients. It is competition. Alphabet, the world’s largest advertiser and owner of YouTube, and Meta are once again trying to break into the e-commerce business. Walmart, which dominates the $2trn American grocery market, is moving zealously into advertising and has launched a Prime-like subscription service that helps it convert purchases into data.

Most threatening of all, Microsoft is widely regarded as having taken the lead on integrating generative AI into its assorted enterprise offerings, thanks to its partnership with OpenAI, the startup at the technology’s bleeding edge (and maker of ChatGPT). If it wants to avoid a mid-life crisis, Amazon will have to show it is the better seamstress. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.