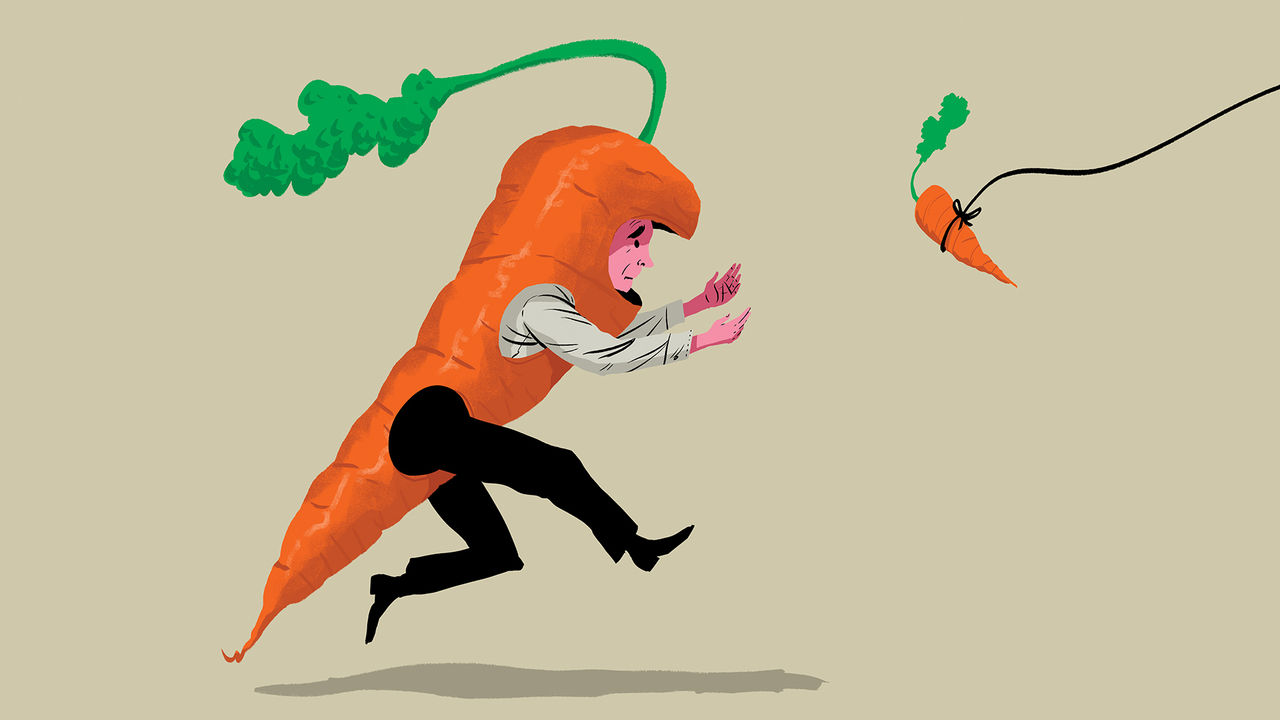

“If you have a dumb incentive system, you get dumb outcomes.” The late Charlie Munger was endlessly quotable, but this pearl of pith from the famed investor is one that every manager should remember.

There are plenty of dumb examples to choose from. Some are apocryphal: the Soviet nail factory that produced a single, uselessly gigantic nail to meet its tonnage quota. Others are not. Wells Fargo, a previously well-regarded American retail bank, was notoriously embroiled in scandal after blunt cross-selling targets pushed its employees to open unauthorised deposit accounts and issue unwanted debit cards. Silly financial incentives in health-care systems can help explain everything from once-elevated rates of Caesarean-section births in Iran to woefully inadequate dental treatment in Britain.

The trouble is that it is not always easy to work out what dumb looks like. A study published in 2017 by David Atkin of the Massachusetts Institute for Technology and his co-authors found that many football manufacturers in Sialkot, Pakistan were oddly slow to adopt a new technology that reduced the amount of synthetic leather wasted during their production. The reason? Workers who were paid by the ball were not keen to spend time that could otherwise have been used to earn money on learning new techniques. In theory, a piece-work incentive scheme makes perfect sense for this kind of repetitive activity; in practice, it was the firm that paid their workers by the hour which quickly embraced the new technology.

A couple of recent studies underline the risk that incentives will have unintended consequences. One, from Jakob Altifian and Dirk Sliwka of the University of Cologne and Timo Vogelsang of the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, tested the effect of paying an attendance bonus on levels of absenteeism. They did so by randomly assigning apprentice workers at a German retailer to two groups which offered a financial reward or some extra holiday, respectively, for a perfect attendance record. Neither reward reduced absenteeism, and the monetary bonus had precisely the opposite effect: it actually increased rates of absenteeism by 50% on average.

To work out what was going on the researchers surveyed employees after the experiment had ended. They found that the introduction of a bonus shifted workers’ perceptions of what counted as acceptable behaviour. The message that attendance warranted a reward made people feel less obliged to come in and less guilty if they threw a sickie. The effect was particularly pronounced for the most recently hired employees, and higher rates of absenteeism persisted even after the bonus had been removed. The power of incentives to change social norms can be helpful: an attendance bonus has been shown to work in circumstances where widespread absenteeism is a real problem. But the starting-point matters.

A second study, by Luan Yingyue and Kim Yeun Joon of the Cambridge Judge Business School, tested the effects of making co-operativeness a formal job requirement. Expectations of being helpful to colleagues were added to the job descriptions and performance appraisals of engineers working in a research-and-development (R&D) centre at a chemicals company in East Asia. (A second R&D centre in the company acted as a control.)

Surveys of affected employees found that the motivation to help changed once it was part of the job, from an intrinsic drive to be co-operative to a desire to show off to the higher-ups. The type of help that people offered their colleagues changed as a result: there were more frequent instances of helpful behaviour but the quality of assistance that people actually gave each other went down. “How can I help as long as it doesn’t involve too much effort?” is a very watery form of collaboration.

These examples confirm both the wisdom of Munger’s aphorism and the difficulty of anticipating how incentives will play out. Dumbness may become apparent only over time, so pilot schemes and rigorous review processes are essential. As Stephan Meier, an academic at Columbia Business School, argues persuasively in “The Employee Advantage”, a new book, people are motivated by many more things than moolah. Rewarding people for doing things they would anyway can easily backfire. As Munger might have said, incentives should be approached like gelignite—with enormous care. ■

Subscribers to The Economist can sign up to our new Opinion newsletter, which brings together the best of our leaders, columns, guest essays and reader correspondence.