Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

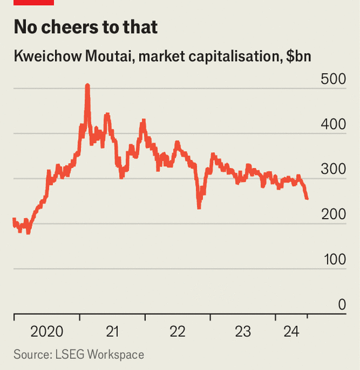

THE ROLE of Kweichow Moutai in Chinese society is complex. The state-owned company’s fiery, translucent baijiu is by far China’s favourite booze. It is one of the country’s oldest brands—a rare corporate survivor of the worst days of Maoism. Vintage cases fetch tens of thousands of dollars. In 2021 it was briefly worth a throat-scorching $500bn and in 2022 it eclipsed Tencent, a digital giant, to become for a time the most valuable Chinese listed company.

Today its market capitalisation is half that. Some of the decline has to do with President Xi Jinping’s crackdown on graft, before which prized bottles of the sorghum-based firewater would often change hands in place of cash. When in 2020 state TV accused Moutai of benefiting from bribery, $25bn instantly evaporated from its market capitalisation.

Yet the most recent slide in the company’s share price, which is down by 14% since early May, does not appear to be related to anti-corruption campaigns. Moutai has not been subject to a recent state media hit-piece or government investigation. Its revenues grew by nearly a fifth in the first quarter, year on year, to 46bn yuan ($6bn). Net profit jumped by 16%, to 24bn yuan. Its margins remain as eye-watering as its booze. What is going on?

The mystery of Moutai has captivated equity analysts, businesspeople and baijiu aficionados alike. Two colourful theories are making the rounds.

One has to do with the woes of formerly prodigious Moutai buyers. Property tycoons, said to have been among the biggest, are in the midst of a particularly severe dry spell. It may be no coincidence that bottle prices and house prices both peaked around the same time in early 2021, as Merchant Securities, a local broker, points out. Moutai’s flagship 106-proof firewater now goes for 2,200 yuan a bottle, from 2,700 yuan at the beginning of the year and 3,100 yuan three years ago.

An even quirkier explanation concerns a card game. Over the past few years guandan (which translates as “egg tossing” or “bomb tossing”) has become a fixture at banquets across the country. It is rumoured that even some of China’s most senior officials enjoy the game, in which two teams of two players attempt to empty their hands by playing high combinations of cards. Richard Liu, who founded JD.com, a large e-merchant, is a self-professed fan.

As a result, guandan skills have become indispensable for business dinners. Just as executives around the world have learned to play golf in order to entertain business partners, many Chinese businesspeople are practising the card game in order to make an impression at banquets. Bloggers in China have speculated that playing cards is replacing competitive drinking as the single most important banquet activity. They note that serious guandan players tend to stay sober. This might be keeping Moutai off more and more banquet bills.

There are more mundane explanations for Moutai’s declining market value. The firm is ramping up production at a time when consumer sentiment is weakening. It has poor control over its distribution. But if Mr Xi’s new economy features fewer property magnates and more young tech founders who view winning at guandan rather than getting sloshed as a prerequisite to signing deals, then this could really stick the knife into Moutai’s future growth. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.