When Tinder, a mobile dating app, launched on college campuses in America in 2012, it quickly became a hit. Although online dating had been around since Match.com, a website for lonely hearts, launched in 1995, it had long struggled to shed an image of desperation. But Tinder, by letting users sift through photos of countless potential dates with a simple swipe, made it easy and fun.

Soon Tinder and its rivals had transformed courtship. A report published last year by the Pew Research Centre found that 30% of American adults had used an online dating service, including more than half of those aged between 18 and 29. One in five couples of that age had met through such a service. Usage surged during the pandemic, as lonely locked-down singles sought out partners. The market capitalisation of Bumble, a rival to Tinder, surged to $13bn on its first day of trading in February 2021. Later that year the value of Match Group, which owns Tinder, Hinge and scores of other dating services, reached nearly $50bn. Today roughly 350m people around the world have a dating app on their phone, up from 250m in 2018, according to Business of Apps, a research firm. In June Tokyo’s government even said it would launch a matchmaking app of its own to pair up singles in the city.

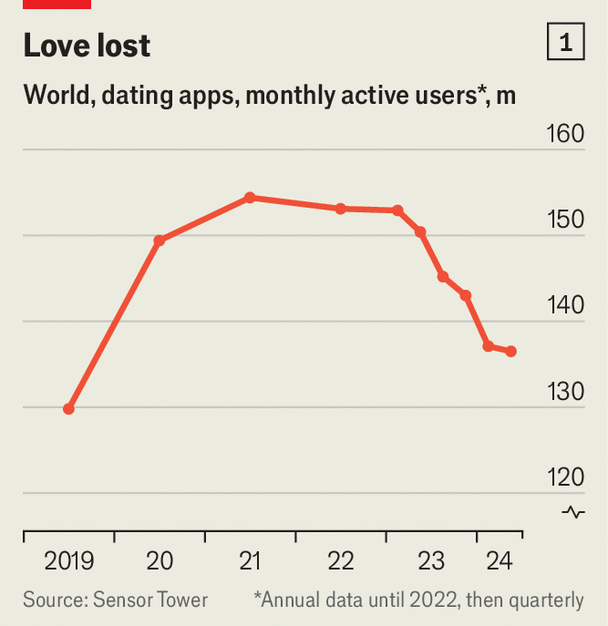

Yet lately online dating has lost its spark. The apps were downloaded 237m times globally last year, down from 287m in 2020. According to Sensor Tower, another research firm, the number of people who use them at least once a month has dwindled from 154m in 2021 to 137m in the second quarter of this year (see chart 1). On August 7th Bumble reported revenue growth of just 3%, year on year, in the quarter from April to June, and lowered its forecast for the full year to 1-2%. Its shares plunged by a third in after-hours trading. On July 30th Match Group reported that its revenue for the same quarter grew by only 4%. Both companies’ market values have cratered since Bumble’s listing (see chart 2). That reflects users’ increasing disillusionment with dating apps, decreasing willingness to pay for them—and growing interest in offline alternatives.

Start with the disillusionment. Apps that once felt fun have, for many, become wellsprings of frustration. The network effects that initially propelled services such as Tinder, in which a widening choice of partners lured in ever more users, have now made them exasperating. Users grumble about spending hours sorting through tens of thousands of profiles. Half of women surveyed by Pew said they felt overwhelmed by the number of messages they received. It doesn’t help that 84% of Tinder users are men. So are 61% of those on Bumble, which is targeted at women. Many users also fret about scams.

Younger adults are growing especially weary of the apps. One survey commissioned last year by Axios, a news site, found that only a fifth of American college students were using them at least once a month. “It’s not fun, it’s so superficial and it’s also just like really exhausting,” laments one youthful influencer on TikTok, a short-video app. “I’m kind of over it,” sums up Wunmi Williams, a 27-year-old who, after years of swiping and matching, has been unable to find a partner through a dating app. In a sign of growing despair, the Marriage Pact, an annual event in which participants are matched with a “backup” spouse should their future romantic endeavours fail, has spread to 88 college campuses across America.

All this helps explain why dating-app developers are struggling to convince users to part with cash—the second reason for their lacklustre performance. In an effort to boost margins, dating apps have been peddling paid upgrades to supplement their lowly ad revenues. Hinge has a separate feed with popular profiles it thinks you might like, but demands that you hand over $3.99 for a “rose” before you can chat with them. Tinder’s paid plans range from $17.99 a month (which gives you unlimited swipes and lets you change your location) to a hefty $499 a month (which lets you see the most popular profiles on the app and message users you haven’t matched with).

Got the ick

Online dating may no longer look desperate, but users seem to worry that paying for it might. The share of people who are willing to spend money on dating apps has been falling. Tinder’s paid users have declined for seven consecutive quarters. Men are more likely to cough up, which may be worsening the feeling common among women of being bombarded by messages on the apps.

Perhaps the biggest threat to the future of dating apps, though, is the growing share of singles looking offline for love. Last year some began wearing an aqua-coloured ring, made by a startup called Pear, to show their openness to being wooed. Thursday, a company that organises in-person events for singles, has expanded its service to roughly 30 cities, from Stockholm to Sydney. Its app works only on Thursday, when the events are held.

The romance is not confined to bars. Running clubs have become a place for athletic types to meet. Cooking classes, too, have become a place to look for partners, says Julia Hartz, the boss of Eventbrite, a ticketing platform. Attendance at its singles events rose 42% between 2022 and 2023. “You are bonding with someone, you’re having an experience, even if they’re not the love of your life,” says Casey Lewis, a blogger on youth culture, of such events.

Dating apps are looking for ways to lure users back. Some are hoping to spice things up with artificial intelligence (AI). Whitney Wolfe Herd, Bumble’s founder, recently mused that the future of courtship could involve one person’s AI bot going on “dates” with another’s. One new app, Volar, has begun offering just that.

In time, society might be willing to leave matchmaking to machines—but it is hard to imagine the strategy paying off just yet. A more fruitful approach for dating apps may instead be to focus on narrower markets. Grindr, an app for gay men, continues to grow quickly. So does Feeld, which targets the polyamorous. In the past few years Match Group has launched apps targeted at gay men (Archer), single parents (Stir), ethnic minorities (BLK, Chispa) and snobs (The League). Revenue from this portfolio of brands grew by 17%, year on year, in the second quarter of 2024.

In addition to offering a smaller pool of partners, such apps also serve as a community for like-minded people. Grindr, for example, acts as a travel guide for tourists looking for gay bars and a hub for information on HIV. The company says its average user sends 50 messages a day, about the same as for WhatsApp, a messaging service. Its success in that regard might explain why Lidiane Jones, the chief executive of Bumble, has said she wants her firm to be known as a “connections company, rather than a dating company”. Pulling off such a rebrand may prove tricky. But love has never been an easy business. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.