FIVE MILLION DOLLARS were on offer to contestants in “Beast Games”, a new game show being made for Amazon’s Prime Video streaming service. Instead, some participants received physical injuries, emotional distress and sexual harassment, according to a complaint filed in a Los Angeles court on September 16th. Amazon and the show’s creator, Jimmy Donaldson, a 26-year-old YouTuber known as MrBeast, have not commented on the lawsuit. But the fiasco has reassured some Hollywood executives that they have little to fear from social-media upstarts.

Should they be so confident? On the face of it, social-media stars are struggling to break into traditional media. MrBeast, who with 316m followers runs YouTube’s biggest channel, is not the only one to have stumbled. Ryan Kaji, a 12-year-old YouTuber, released a feature film last month which bombed in theatres. Disney’s reality show about the D’Amelios, a TikTok dynasty, was cancelled in June. Television presenters such as Tucker Carlson, who makes a show for X, have embraced social media only after being dropped by the mainstream sort.

But in the battle for viewers and advertising dollars, the amateurs are increasingly beating the pros at their own game. Americans now spend more time watching YouTube on their televisions than any other source of content, according to Nielsen, a data company (see chart 1). Worldwide, 2.5bn people tune in monthly. When YouTube’s chief executive, Neal Mohan, boasted in May that “creators are the new Hollywood”, some in Tinseltown scoffed. But admen are listening, and syphoning TV budgets into the medium. As social media and television blend into one, two previously distinct markets are being thrown into fierce competition.

The gap between user-generated video and television is real, but narrowing. “It’s way bigger than just a bunch of guys in their bedroom filming,” says Jordan Schwarzenberger, manager of the Sidemen, a group of seven British YouTubers with a combined subscriber-count of more than 100m. The group has a staff of 40, from set designers to thumbnail-graphic artists, based in a studio in Hoxton. Their weekly videos of an hour or two often have six-figure production budgets; a trip to shoot three episodes in America cost millions, says Mr Schwarzenberger. The group’s biggest revenue stream is the 55% cut of advertising revenue that YouTube gives to creators who clear a popularity threshold. Like MrBeast, the Sidemen are exploring sidelines, including a restaurant chain and a vodka brand.

Few YouTubers have such a sophisticated setup, but professionalisation is becoming more common. In Britain alone more than 15,000 creators employ others to work on their YouTube channel, the video site estimates. Technology is raising production quality. “The tools are becoming much more sophisticated…and it really is blurring the lines of what I would call independent and studio-backed content,” says Mary Ellen Coe, YouTube’s chief business officer. Hardware such as 4K cameras and software for special effects has got cheaper. Drones stand in for helicopters. Artificial intelligence promises to unlock more professional-grade features: “Aloud”, an AI-powered dubbing tool made by YouTube, already lets creators switch between English, Spanish and Portuguese.

Audiences, meanwhile, seem to be turning to social media for the kind of programming they once got from television. A survey of the videos on YouTube’s “UK Trending” page by Enders Analysis, a research firm, found that about 60% of views were of genres usually associated with traditional TV, such as drama and sport. Videos are getting longer, too: nearly a third of videos on the UK Trending page today last between 20 and 60 minutes—about the length of a TV episode—up from a tenth in 2020. And whereas traditional TV is increasingly available on-demand, with catch-up services such as the BBC’s iPlayer, social media is becoming more linear. Live streams are the third-most popular genre of online video (after music and comedy), watched by 28% of internet users, according to a report by Kepios and GWI, a pair of research firms.

Social media may not have seemed like a rival to Hollywood while it was confined to computers and smartphones. But it has begun to colonise the living room. Close to 45% of YouTube viewing in America takes place on TV screens, according to a report last year by the Information, a news site. YouTube says that among its 100 most watched channels worldwide, more than 40 count the television as their most watched screen. Other social platforms are trying to pull off the same trick: TikTok launched a TV app in 2021 (which has struggled, partly owing to its vertical videos); X released one on September 3rd. Hollywood is responding with a counter-invasion of mobile, particularly in countries where internet-connected TVs are scarce. Of the half-billion Indians who watch streaming video, 81% do so only on a smartphone, according to Ormax Media, a research firm. Streamers such as Netflix and Disney+ have launched mobile-only plans in developing markets.

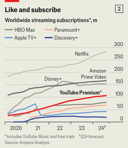

With increasingly similar content, delivered on the same devices, it is no surprise that new and old media’s business models are also overlapping more. The bulk of YouTube’s revenue last year came from $32bn in advertising sales. But it has also been pushing ad-free subscriptions, for $13.99 a month. In February the company announced that it had passed 100m subscribers (albeit including some on free trials), putting it ahead of many Hollywood streamers (see chart 2).

At the same time, streamers that are historically subscription-driven have been pushing into advertising. Netflix and Disney+ launched ad-supported tiers in late 2022; Amazon followed suit earlier this year. For now, advertising remains a small part of their business. Although nearly half of new Netflix members are signing up to the ad tier, as of May its ads were reaching only about 40m viewers per month, less than 2% of the number reached by YouTube. Amazon has made a bigger splash, imposing ads on all 160m or so of the households that watch Prime Video, unless they pay extra to avoid them. Amazon is also the only streamer that can compete with YouTube in terms of ad-tech expertise and depth of customer data, where it rivals YouTube’s parent company, Google.

The battle for audiences and ads is heating up. As broadcast and cable television wane, video advertisers are looking for a new home. TV commercials made up a third of all ad spending in America in 2019, but this year will make up only a fifth, according to MoffettNathanson, a firm of analysts. Many advertisers still see social media as a different channel from traditional television. “There’s this comfort level with TV having been the dominant medium for so many years,” says Jasmine Enberg of eMarketer, a research firm. “Consumers aren’t as concerned as to where they are watching videos…but marketers just haven’t quite caught up there.”

The more that platforms like YouTube can highlight their TV-like content, the easier it will be to unlock those TV advertising dollars. Yet this professionalisation has a cost. Over the past three years YouTube has paid out an average of $23bn a year to creators and media companies—substantially more than the $15bn that Netflix is expected to spend this year on its shows and movies. And whereas Hollywood studios’ content spending is fixed, YouTube’s revenue-sharing model means that its costs rise in tandem with its ad revenue. In Britain, for example, the number of YouTube channels earning more than $10,000 a year has risen by 30% in the past 12 months, the company says. As social platforms get closer to Hollywood quality, they are taking on blockbuster costs, too. ■

To stay on top of the biggest stories in business and technology, sign up to the Bottom Line, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.