REACTING to a takeover offer is a delicate moment for any company board. For the leadership of Seven & i, the Japanese owner of 7-Eleven, a convenience-store chain, the burden of responsibility is even greater. Its response to what could become the largest ever foreign acquisition of a Japanese firm represents a pivotal moment in the country’s corporate-governance revolution.

On September 6th the board of Seven & i rejected a $38.5bn takeover offer from Alimentation Couche-Tard, a Canadian retail giant which owns the Circle K chain of stores. Seven & i, which was worth around $31bn before the offer, said the bid undervalued the company and that the merger could face regulatory hurdles in America. The deal is not dead yet. On September 9th the Canadian buyer reiterated its interest and asked Seven & i to engage in discussions.

That a company such as Seven & i might even consider selling itself would have been unthinkable a little over a decade ago. Japan’s listed firms have long been known for their hostility to takeovers and their lack of responsiveness to shareholders’ demands. That has been slowly changing. Reforms to corporate governance were a major component of Abe Shinzo’s political platform when he became prime minister for a second time in 2012. His government published a new governance code in 2015, which has begun to yield results. According to rankings from the Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA), an advocacy group, Japan’s corporate governance has risen from fifth place in the region in 2020 to second in 2023, behind only Australia’s.

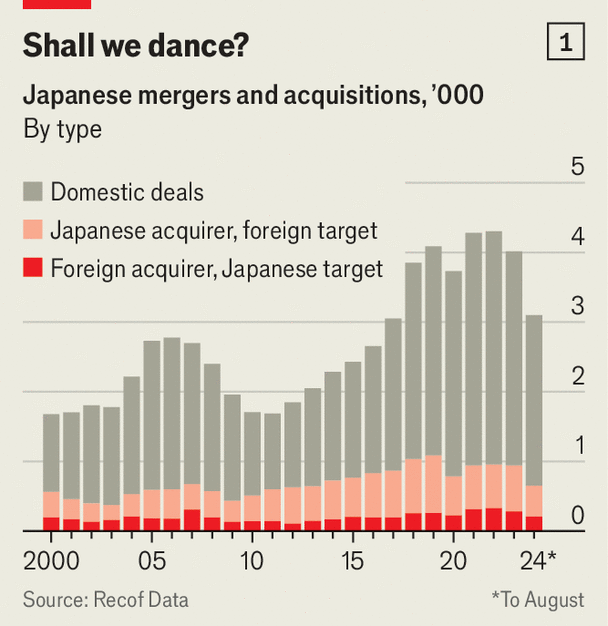

Japan’s reforms mean that listed firms can no longer simply dismiss takeover attempts out of hand. That has fuelled a surge in dealmaking. Between 2013 and 2023 the number of mergers and acquisitions involving Japanese firms doubled, to around 4,000, according to Recof Data, a research firm (see chart 1).

Webs of cross-holdings among Japanese companies, once used as a means to fend off hostile takeovers and cement commercial relationships, are also being unwound as new rules have forced firms to explain the rationale for them. Last year 8.4% of the assets of Japan’s 500 most valuable firms were in the shares of other companies, down from 13.5% eight years before, according to the ACGA. In June Toyota, a Japanese car giant, said that it had sold around $2bn in shares in other firms in its fiscal year ending in March.

Activist-investor campaigns, once rare in Japan, have blossomed as well. There were 103 of these campaigns last year, up from just 14 in 2013, according to Diligent Market Intelligence, another research firm (see chart 2). Activists have been encouraged by a string of successes. In February last year Elliott Management, one fearsome gadfly, prodded Dai Nippon Printing, a Japanese industrial firm, to buy back a slab of its shares. A month later Oasis Management, a Hong Kong-based activist, hounded Fujitec, an elevator manufacturer, into ousting its chairman; the liftmaker’s share price is up by a half since then.

Yet Japan’s corporate-governance crusade is far from complete. Deals may be up, but transactions are typically small and most of the action is among Japanese firms only; mega-deals, particularly involving foreign companies, remain uncommon. Cross-holdings are still a bugbear of investors. And returns on investment continue to be meagre. Last year listed Japanese firms generated a return on equity of 8%, compared with 10% for European firms and 14% for American ones.

All that helps explain why Japanese firms’ valuations are so low. Their average price-to-book ratio, which measures a company’s market capitalisation relative to the book value of its assets, is just 1.5 times, and has changed little over the past decade. The equivalent figure is 2.1 times for European companies and five times for American ones. What is more, about half of Japan’s listed companies have a price-to-book ratio of below one, suggesting they would be worth more if they were broken up and sold for parts.

Such laggards are now in the sights of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, which has taken up the mantle of reform as Japan’s politicians have shifted their focus elsewhere. It now requires companies with a price-to-book ratio of less than one to list what actions they will take to improve their performance. Although four-fifths of firms in the prime market (made up of Japan’s largest and most liquid stocks) had disclosed their plans by the end of July, only a third of those in its standard market (made up of smaller firms) had done so. Japan’s corporate giants may be slowly heeding the call for reform, but it will take time for change to filter through. ■